Knobkerries are straight, wooden clubs with a knob on one end. Together with assegais (throwing spears), they are the symbols of various African nations. These two weapons are part of the South African Coat of Arms, introduced in April 2000. Similar versions of such sticks with or without a knob on one end are commonly used in many countries. In Eastern Africa, they are called Rungu. Irish have a very similar version to a knobkerrie, and they are called ‘shillelagh.’ Americans call them rabbit sticks; for Australians, these are throwing sticks. Knobkerries in various versions are also widely used in various Nguni nations, like Zulu, Ndebele, Tsonga, Sotho, and others. However, this article concentrates on knobkerries, as presented at the Ilala Weavers Museum in Hluhluwe, Kwa-Zulu-Natal.

Usage of Zulu knobkerries

Ceremonial function

In traditional Zulu kraals, carrying an assegai (short spear) was contrary to etiquette when entering a superior’s hut. Furthermore, using the real assegai in Zulu dances was also contrary to etiquette. In these dances, the various operations of warfare and hunting were imitated; the performers had something to replace an assegai. Therefore, knobkerries of about the same length as assegais were used. Knobkerries were and are exchanging assegais in their representative or ceremonial functions.

.

.

Walking sticks

Based on the representational function, longer knobkerries with a more suitable handle for holding the stick were developed and commonly used by older men as a walking aid. They are often intrinsically carved or decorated with beads or copper braiding below the neck or in the middle.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Weapons for hunting and self-defense

Young Zulu men in rural areas like hunting in small parties and with lots of dogs. Rock Dassies (Procavia capensis) and Cape Porcupines (Hystrix africaeaustralis) are their target animals. To dispatch these animals, they use knobkerries.

Zulus also take their knobkerries when they go after game birds. The general plan is for two men to hunt in concert. They walk some fifty meters apart. They rest their Kerries on their right shoulders when they reach a potential hunting area. This way, they lose no time drawing back the hand when they wish to fling the weapon. As soon as a bird rises, they simultaneously hurl their Kerries at it, aiming slightly above the bird and below. If the bird catches sight of the upper club and dives down to avoid it, the lower club takes effect. When it rises from the lower Kerrie, it falls victim to the upper.

For self-defense, a knobkerrie can be employed as a weapon with which an opponent can be struck directly. It can also be used as a missile, flung straight at the antagonist. Moreover, knobkerries will sometimes be thrown on the ground so that their elasticity causes them to rebound and strike the enemy from below instead of from above.

In another article on this webpage, we described using a Throwing stick (called Kerrie), which is similar to a Knobkerrie but curved and without a knob.

Decapitation knobkerries

Although called ‘decapitation knobkerries,’ they were not used for decapitation but for smashing the skulls of enemies, prisoners of war, or even own people committing certain crimes. They had a short, stout handle and a heavy knob. On antique decapitation knobkerries, traces of blood can still be found under UV light.

From which materials are knobkerries made?

Traditional Zulu knobkerries were made from the wood of Tamaboti (Spirostachys africana) or Bloodwood / ‘Kiaat’ in Afrikaans (Pterocarpus angolensis). Other sources insist that Zulu used “Knobthorn” (Acacia nigrescens) wood for that. The long walking stick knobkerries were carved from Stinkwood (Ocetea bullata).

Before 1880, the most valuable and durable knobkerries were cut from white rhinoceros horns. Knobkerries made from this material were highly valuable because killing such an animal and the labor necessary to carve the Kerrie from that hard material was difficult. Luckily, these times are long over, and Rhinos are strictly protected.

Knobkerrie collection at the ‘Ilala Weavers Museum.’

The Sutton family has been trading Zulu handcrafts since the early 1970s and has collected a variety of knobkerries. They present these to the public at their ‘Ilala Weaver Museum’ at Hluhluwe. The museum is more of a sales showroom of fine original handcrafts but contains a variety of museum-grade artifacts, one of which is the Knobkerrie collection. For a link to this museum, see here.

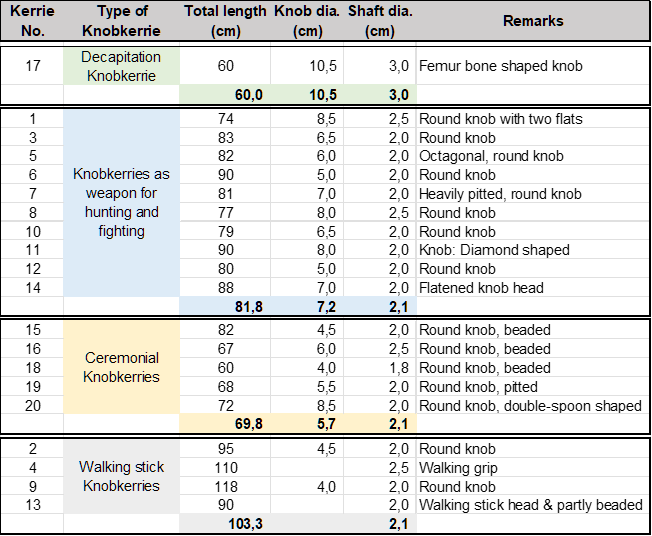

I asked the attendant if taking photos of these knobkerries and measuring them would be possible. She agreed, and the results are shown in the following table. Knobkerrie numbers were counted from left to right of the photos.

Mr. Shiloh Noone, owner of the Matshana Museum in Hermanus and expert in Zulu war artifacts, doubted in personal communication with the author that all knobkerries in this collection are of authentic Zulu origin. He suspects that some Shona and Swazi knobkerries are also intermingled. Furthermore, one of them could even be of Central African origin. The exact allocation of each knobkerrie to certain tribes could only be done after a thorough examination.

General sizes of each category

Nevertheless, regarding tribal allocation, the four categories of knobkerries are the same as discussed above. Therefore, the following generalizations can be taken:

As can be seen in the table, knobkerries, for ceremonial purposes, have got a total length of about 74cm / 2.4ft, got a knob diameter of about 5,5cm / 2.2’’, and a shaft diameter of usually 2cm / 0.8’’.

Knobkerries used as walking sticks are longer – about 1m /3.2ft long – and have the same shaft diameter. Moreover, knobkerries for hunting and self-defense are, on average, 82cm /2.7ft long and got the same shaft diameters but got a heavier knob, which is, on average, 7,2cm /2.8’’ wide.

Considerable differences between these three applications are decapitation knobkerries for clubbing/executing enemies. They are max. 60cm /1.97ft long, but got a more robust handle and a big, hefty knob. In our example, this knob has a diameter of 10,5cm / 4.1’’.

Lessons learned about knobkerries at Ilala Weavers Museum at Hluhluwe:

- Ceremonial sticks are often carved or decorated with glass beads or copper braiding.

- Long, slender ones, often decorated intrinsically, are used as walking sticks or for ceremonial purposes.

- Knobkerries as a work tool for hunting or self-defense are typically about 82cm / 2.7ft long, got a knob with abt: 7,2 cm /2.8’’ diameter and a handle thickness of 2cm /0.8’’.

- Short, stumpy knobkerries with a heavy knob were used for executions.

- Copper braiding was also used on decapitation knobkerries from the 1800s during the Ceteswayo rule when the Zulus traded with copper in Delagoa Bay.

.

2 comments

Kurt Hoelzl

Highly appreciate your comment. I have already set this article’s visibility to private (not public anymore) until a historically correct version is available, and I also sent you an email for further clarification.

Shiloh Noone

Please note a lot of those knobkerries are not zulu and many very modern. Shiloh Noone Matshana Museum