Roof thatching is vital for shelter waterproofing in the Mentawai tribe, which has around 6,000 members, on Siberut Island, Indonesia. Siberut lies about 100 miles (160 km) west of Padang in West Sumatra.

Of the 6,000 Mentawai people, roughly 1,000, mainly elders, live traditionally in the Evergreen tropical forests. The younger generation attends schools and must adopt recognized Indonesian religions, leading to a loss of cultural ties. Consequently, they may settle in villages outside the forest. As a result, most traditional family houses might deteriorate, and vibrant shamanism could give way to tourist-oriented hip-hop dances in the future.

Our group consisted of an English-speaking Mentawai interpreter, a temporary porter, and myself. We spent four nights at Aman Aru’s Uma in the Buttui area and visited another Uma during our stay. Everything you see in these articles about the Mentawai tribe’s skills—clothes, decorations, tools—is authentic and part of their daily lives. For my visit, there were no artificial displays or fabrications.

Roof thatching for two types of Mentawai shelters

The traditional Mentawai lifestyle involves two shelters: the family house (Uma), where the extended family gathers for living or ceremonies, and forest camps, which cater to single, older individuals or hunters.

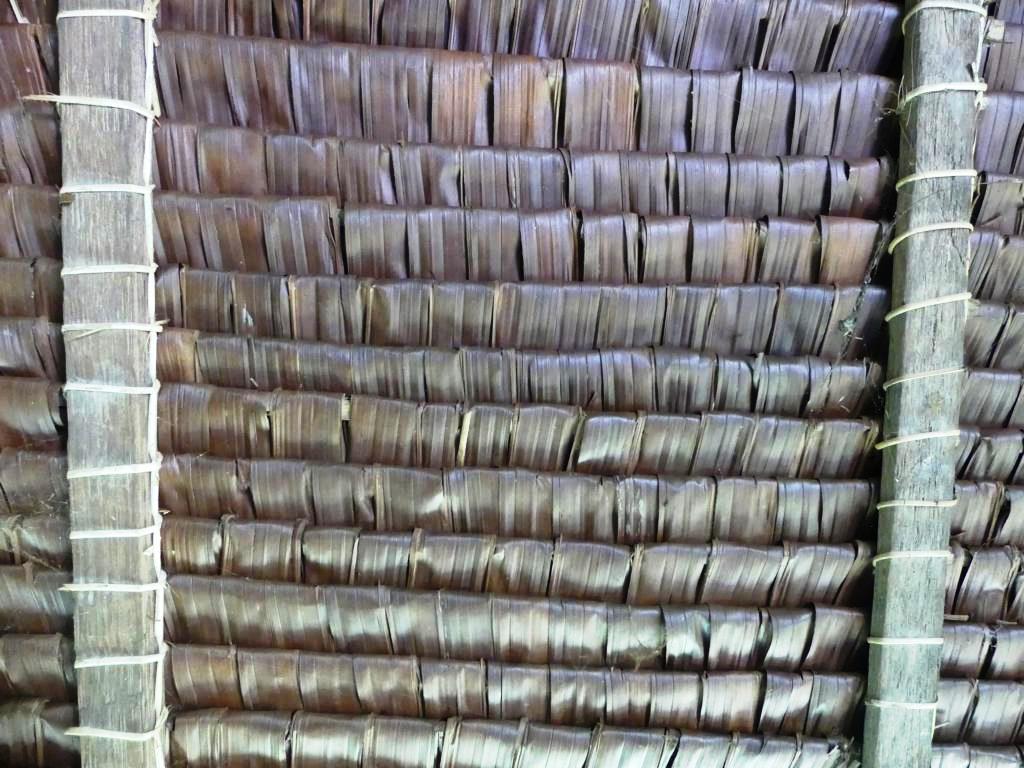

Both shelter types utilize palm leaf panels stacked atop one another for roof thatching. In Umas, these panels rest around 2.8 inches (7 cm) apart, while in forest camps, they’re double that distance. The Uma roof lasts over 20 years, but insect activities may affect its lifespan. When natural materials are used, the roof gable needs replacement or reinforcement every five years.

.

Materials for making the thatching panels

Three specific natural materials are essential for making a thatching panel:

- Bamboo Stave:

- A 2-meter-long, 2-centimeter-wide, flat section of straight bamboo from the Maggeak (local Mentawai name) species with thin stem walls and long internodes. This bamboo piece serves as the holder for the thatching leaves.

- Rattan Vine:

- A piece of rattan vine, approximately 4 mm (5/32 inches) thick, split in the middle. Both sections, each about 1 meter longer than the bamboo stave (around 3 meters), are used in making the panels. Mentawai name of this rattan species is ‘P

elege‘ (Calamus javensis)

- A piece of rattan vine, approximately 4 mm (5/32 inches) thick, split in the middle. Both sections, each about 1 meter longer than the bamboo stave (around 3 meters), are used in making the panels. Mentawai name of this rattan species is ‘P

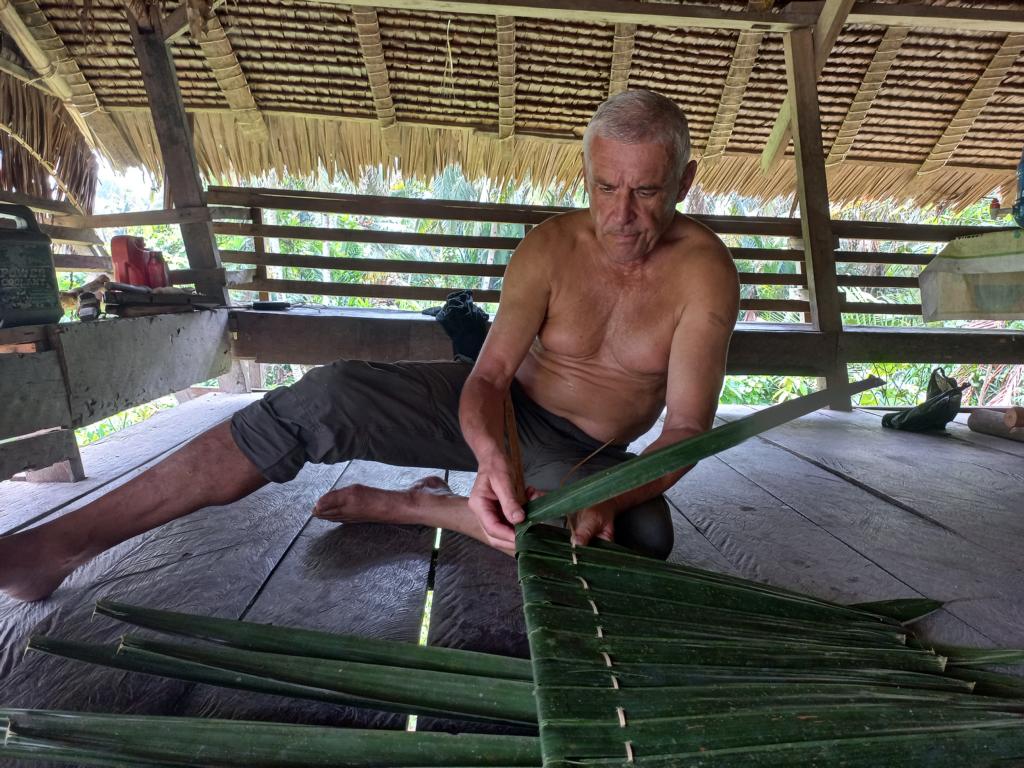

- Sago Palm Leaflets:

- The leaflets from pinnately compound sago palm (Metroxylon sagu) fronds serve as the actual thatching material.

Assembling procedure

Describing the process of binding the leaflets onto the stave might be confusing, so I’ll showcase this procedure in two upcoming videos. The first video will demonstrate how to bind the initial leaf, which is quite similar to the process for the final leaf.

Video: First leaf binding

The second video shows the binding of all other leaves between the first and last one.

Video: Further leaves binding

To create a durable and waterproof palm leaves panel, the following points are crucial:

a_Each new leaf should overlap the previous one, aligning its margin with the midrib of the last installed leaf.

b_When folding the new leaf over the stave, bend the midrib carefully at a 90-degree angle until you hear a slight breaking sound, then bend it another 90 degrees into the new position.

c_Sew the rattan vine before and over the midrib from both the top and bottom of the panel. This ensures the vine consistently presses down on the leaf’s midrib from alternate sides.

Installation of palm leaf panels

The finished panels are installed on the wooden roof frame from bottom to top, using the same rattan vines used for the panels themselves. In a Uma, with panel distances of about 13 cm / 5” and standard lengths of sago palm leaflets, a roof overlap of 7 layers of leaf panels is achieved at every point. This design ensures effective rainwater drainage from the hut’s interior, offering deep shade and thermal insulation against heat and sun. The palm leaf layer allows hot air to dissipate, ensuring a healthy climate inside the shelter. Although insects may nest on the roof, various gecko species naturally control their population.

The roof gable area poses a challenge in preventing water seepage. Traditionally, the Mentawai people use complete sago palm fronds placed directly atop the gable to divert rainwater toward the roof panels. Wooden knee frames secure these fronds, as depicted in the picture above. In more contemporary huts, bent sheet metal safeguards this crucial roof section and offers higher durability.

Key Takeaways from Mentawai People’s Palm Leaf Panel Assembly:

1_Sago palm frond leaflets are the primary material used for roof thatching.

2_The most suitable rattan vines for binding are sourced from the surrounding Evergreen tropical forest.

3_Careful bending and overlapping of sago leaflets ensure a secure fit over installed leaves.

4_Binding with rattan vines effectively secures the midribs in place.

.