Termite mounds are primarily made of soil, excavated below the mound, and carried to the surface by these insects. They use the soil to construct the mound, forming it into various shapes depending on the termite species. The exterior of the mound is usually coated with a hard, clay-like substance that helps to protect it from the elements and predators. Termites produce this substance by mixing soil with secretions from glands on their bodies. They also use saliva as a binding agent, holding the substance together.

In another article on this website, we discussed the use of ‘ant hill’ material for construction purposes in Australia. Another article discusses the general structures of termite mounds and reasons why the tips often point toward the North.

As in Southern Africa, various termite mound shapes and soils were seen; I wanted to check randomly to see if all termite mound soils are suitable as building materials.

These tests were not done in a strictly scientific way, as the number of samples was far too low, and no in-depth measurements were done. But the intention was to get a first indication with simple tests if all termite mound soils can be used as a construction material—either on its own or in a mix with cement or mortar—as implicated by various scientific literature. Examples can be seen here, here, and in many other publications.

Samples were taken from the following locations:

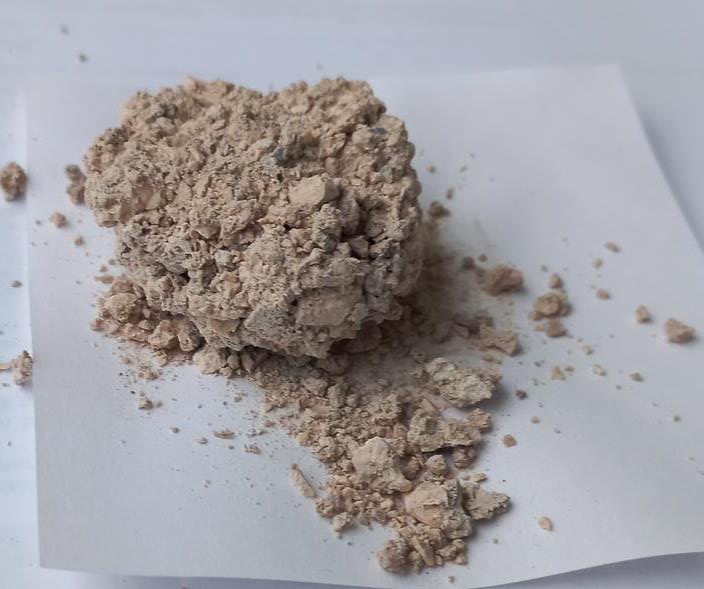

Sample A: This sample was taken in Namibia, Otjozondjupa Region, the eastern side next to B8 Road, 5 km northeast of Grootfontein. Active termite mound. A fist-sized sample was taken from a freshly built-up termite mound tip. The color of the mound was reddish, but the sample turned out to be greyish when processed in Europe.

Sample B: South Africa, Mpumalanga Province, Three Rondavels, 100 m below the parking lot of the ‘Lowveld View’ near Leroro-A village. Inactive and on-surface eroded termite mound. A fist-sized sample was taken from near the tip below the surface. The color of the mound was khaki, but the sample turned out to be a deep brownish-red when processed in Europe. There is no mix-up of samples A and B. The Color change of these two samples seems to be based on different humidity levels between South Africa and Austria.

Sample C: Namibia, Kunene Region, Etosha National Park, southern side next to C38 Road, 22 km west of Fort Namutoni. Inactive and broken-up termite mound. The fist-sized sample was taken from the clay-coated outer surface in the lower region. The color of the sample remained the same as the color of the mound when processing.

Sample processing

Back home in Austria, I processed the samples by first crushing them. Samples A and B could be easily broken down in a mortar. Sample C was so hard that a heavy hammer had to crush it.

Samples A and B were mixed with water and put into round paper carton molds for drying. Only the fraction <5mm was used from sample C, although pounding, heavy, and coarse grains remained. This fine fraction was again mixed with water and put into a paper carton mold.

After drying all three samples for three days at 25 deg C until they were as dry as possible, the remaining humidity was unknown, but all three samples appeared completely dry. In samples A and B, there was a considerable change in the colors of the samples compared to the color of the termite mounds from which they originated.

Sample hardness characteristics

After de-moulding, it was attempted to break the re-hardened termite soil discs in the middle as a hardness test. The results were as follows:

Sample A: The structure was dense, with no delicate pores but some big pores from trapped air. The sample contained dry grass, which further acted as a reinforcement. The necessary force to break the disc was like a thick piece of chocolate of similar dimensions. I was near my limit of power to break the disc in half.

Sample B: The structure appeared spongy and contained many delicate pores. The force necessary to break the disc was roughly half that of sample A.

Sample C: There was nearly no gluing effect between the grains, and the disc crumbled away on handling. No force was needed to break the piece.

Sample behavior on water and application proposals

The behavior of Sample A

When putting sample A into a small puddle of water, the half-disc thoroughly sucked up water within six minutes, and some of the material crumbled into small grains. After water evaporation, the remaining disc and crumbled grains rehardened again. This material could be ideally used for hard-wearing surfaces indoors, like bottom floors of huts.

The behavior of Sample B

When putting sample B into a small puddle of water, the whole half-disc thoroughly sucked up water within ten seconds, and more material – compared to sample A – crumbled into fine grains. After water evaporation, the remaining disc and crumbled grains rehardened again.

That means this material is very prone to erosion by water and is therefore not suitable for building applications that come into contact with water. Also, due to its middle-high strength, it should only be applied to non-hard-wearing surfaces for indoor use. However, it could be used as a plaster on walls to keep out insects, especially if these plastered walls were ‘papered’—as the old colonists in Southern Africa called it.

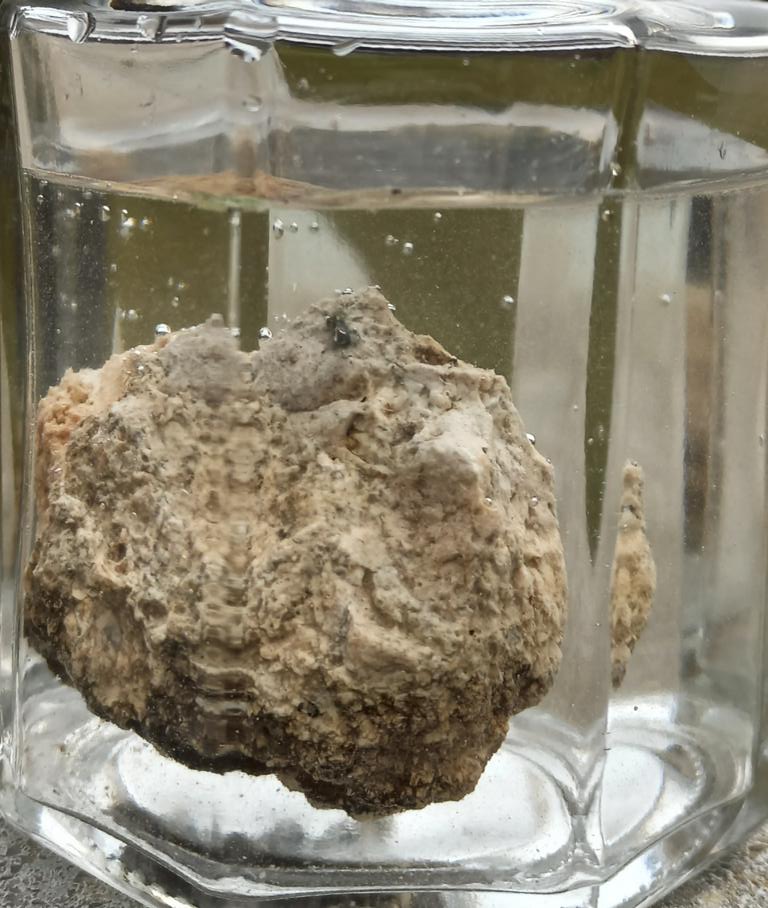

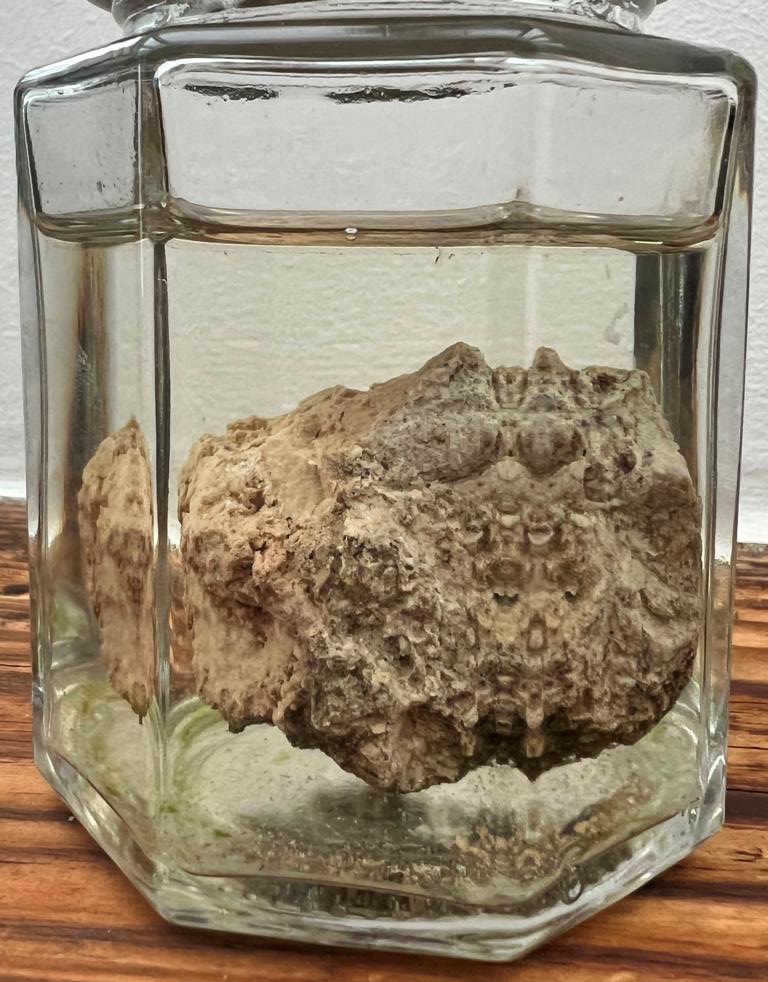

The behavior of Sample C

When I put sample C into a small puddle of water, no water was visually absorbed. Therefore, I fully immersed a lump of sample C underwater. After being immersed for 20 days, no visual deterioration of the lump could be seen. Just very few single grains spalled off.

This material is very hard-wearing, not prone to erosion by water, but does not stick together on its own. It, therefore, could be used as a replacement for rocks and gravel together with cement for creating concrete for hard-wearing surfaces outdoors, like stamping grounds in front of huts, grain silos, water tanks, and similar applications.

Summary

These simple, indicative tests with three different samples showed it clearly. No termite soil is comparable to another termite soil from a different area. Even on the same termite mound, materials from the outside layer and from under this outside layer behave differently. All materials are highly useable for the local population, either as building materials or as an aggregate for mixing with cement or mortar. But before using it for building applications, the above-described simple tests should be applied if somebody does not have local knowledge of a particular area. Locals will know through lore and traditions which part of termite mounds in the area can be used for what application.

When extracting termite soil from a mound, not more than one-third of the mound’s material content above the surface should be removed. Up to this limit, a healthy termite colony can close the gaps relatively quickly to keep mound ventilation and protection against predators (mainly ants) functioning.

Lessons learned from termite soil as building material:

- Mineralogical content of termite mounds depends on the soil they are built on.

- Every termite mound consists of inner material, outer material, and outwash pediment material at the foot of the mound.

- Three samples were taken, each with different characteristics for different building applications.

- When harvesting termite soil from a mound, not more than one-third of the material content above the surface should be removed.

.