Giant Fennel (Ferula communis) is a common weed in Mediterranean countries and Central Asia. Except for one genetic variety in Sardina, all green parts of the plant are strongly haemotoxic and lead to the poisoning of livestock and humans. This hemorrhagic syndrome is known as Ferulosis. The dry, wooden stalk is used for various implements and supposedly for transporting fire. This, however, could not be proven. The following article focuses on using the dry, wooden stalk as a building material.

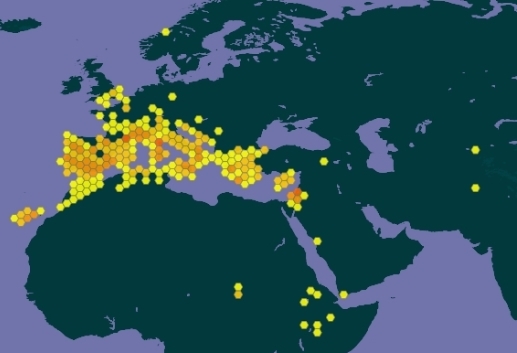

Description and distribution of Giant Fennel

When young in spring, Ferula communis looks exactly like Wild Fennel. The only difference is that its leaves do not smell like anise or fennel. As it ages, an inflorescence develops, reaching up to 4 meters high. The umbellifer flowers are colored deep yellow and resemble a ball. A detailed botanical description of the plant can be found here.

The Giant Fennel’s native distribution is concentrated in the countries on the northern and eastern sides of the Mediterranean Sea, plus Marocco and Algeria. In the meantime, an invasion occurred in the UK, Eastern Africa, PR China, and other countries where hobby gardeners planted this exotic species.

Characteristic of Giant Fennel dry stalk wood

The inflorescence stalk of Ferula communis will dry out over the winter, and for the following six months, these dry stalks can still be found standing. This is the plant material (‘wood’) used for building furniture.

General description of its composition

When breaking apart these stalks, a thin layer of fibers standing man-on-man as an outermost layer is only covered by weatherproof skin. A mixture of spongy material and evenly distributed fibers fill up the remaining area within this ring of fibers.

Wood raw density

The first thing noticed when lifting a Ferula leaf stalk is the lightness of the material. It feels extraordinary to hold such light wood and nevertheless get the impression of inherent strength. I, therefore, determined the raw density. This raw density of a piece of timber includes its moisture, pores, insects, and whatever could be trapped in the wood.

In March, I collected a healthy-looking, fully mature inflorescence stalk at a Nature Reserve near Bronte, ME, Sicily, Italy. I cut out the best-looking portion from that whole stalk and did various tests. The remaining humidity in this test portion of the stalk is unknown, but it appeared to be bone-dry. Therefore, we can assume a moisture content of about 12%.

After that, I cut out a 10 cm long cylindrical piece of the stalk. The cross-section of this stalk was not round but oval. Therefore, I had to calculate an ellipse and multiply it by the average length of the cylinder, which resulted in the cylinder volume. Measuring the exact weight and dividing it by the volume resulted in this material’s Raw density or Specific weight, which is 0,15 g/cm3 or 0.0867 ounce/cubic inch, which has the same density as balsa wood. Pine wood’s raw density is 0,52 g/cm3 or 0.3006 ounces/cubic inch.

Shore hardness

The next test was supposed to determine the hardness of the sidewalls and the inside of the wooden stalk. A so-called Brinell test determines wood hardness in the lumber industry. This test was initially developed for the metal industry and is unsuitable for lightweight materials. Rubber and polymer products are tested by a Shore-D test, where a needle-like structure is used to insert the material and measure the resistance to penetration. I did the same over the whole cross-section of an inflorescence stalk and averaged out the resulting numbers. Finally, I got the following hardness profile.

It can be seen that the rigid outer ring tapers down to the softest portion of the inside material. Only in the middle of the stalk does the material hardness increase again.

Flexural strength

Determining the flexural strength was the most straightforward but most surprising test. I took a 50cm / 20’’ long piece of wooden stalk, propped it up between two elevations on a rock, and stepped down in the middle. I weighed 82kg / 180 pounds, and the stalk diameter was 40mm / 1.6’’. Then, I moved my body up and down to get some dynamics into the equation. The stalk was not squeaking or bending or whatever. It was just holding me up properly without any harm to him. I could now calculate fiber strength, moment of resistance, and so on. But it should suffice to say that this is nearly a wonder of nature. Such lightweight and robust composite material is something mankind still has to invent.

Uses of Giant Fennel stalk wood

Giant fennel stalks are primarily used to produce simple furniture items. Most famous are Sicily’s milk stools, Furrizzi, derived from the name of Ferula. These ‘Furrizzi stools are very lightweight and structurally strong and are only produced by a handful of people nowadays.

Other applications of Ferula stacks are slats for hanging clothes, food, and other items. In former times, teachers also used them to give less-interested pupils some good hiding without seriously hurting them. However, these times are over. For Bushcrafters, Ferula wood in the Mediterranean and Central Asian areas can be used to build furniture, like stools, beds, tables, etc.

Lessons learned from Giant Fennel stalk wood as building material

- Nearly all green Giant Fennel plants are poisonous and should never be eaten.

- The dried inflorescence stacks are very lightweight and structurally very strong.

- Primarily, simple furniture items are built from them.

.