Vine Snakes (previously called Twig or Bird Snakes) are widespread across Africa and are usually found in warm savannas and forested areas. There are currently four species and one subspecies of Vine Snake in Africa. The status and distinguishing features between Oates’ Vine Snake, the Southern Vine Snake, and the Eastern Vine Snake are not well defined, and identification remains tricky between these three species.

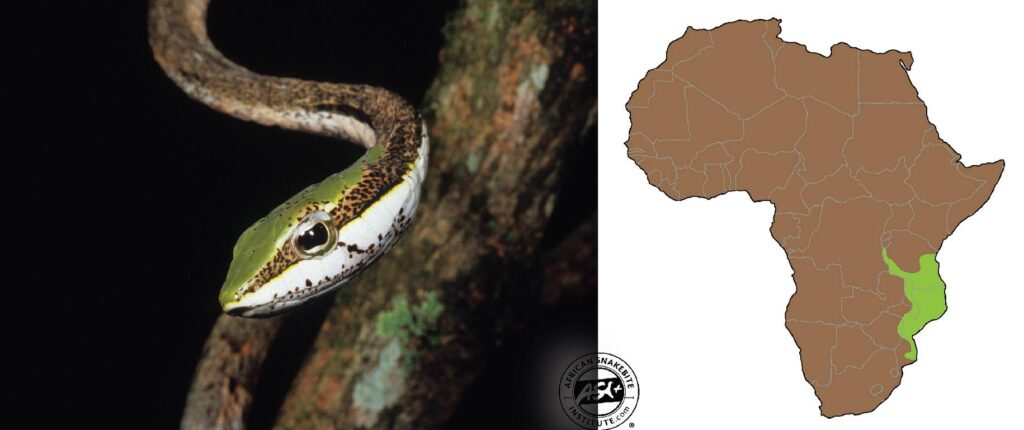

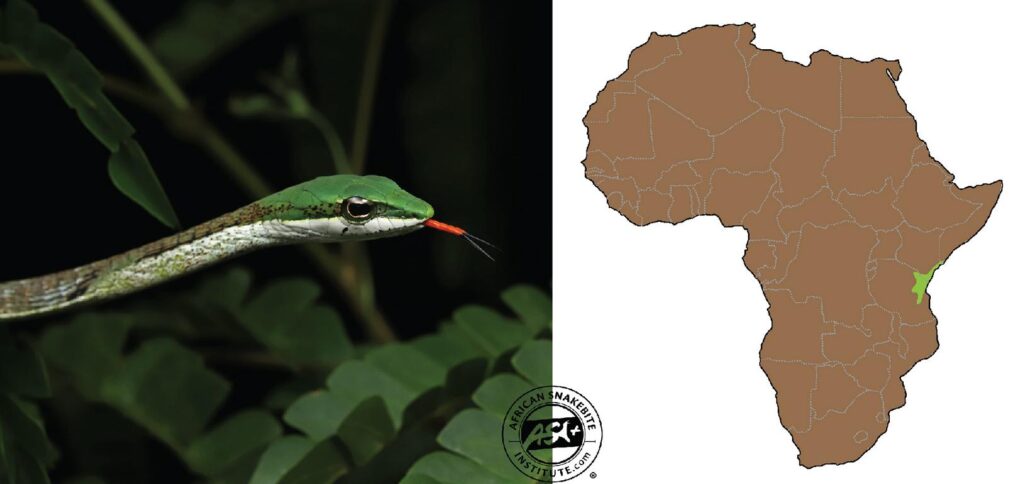

The Latin genus name Thelotornis roughly translates to “a desire to be cylindrical”. They are slender and elongated snakes and very cryptically colored, usually ash-grey or grey-brown, with lighter patches and dark markings across the body. The head is usually green above, notably so in the Usambara and Forest Vine Snake. The Southern, Oates’ and Eastern Vine Snake usually have a green head with a rich brown Y-shape pattern on the crown. The eye of the Vine Snakes has a distinct dark horizontal key-hole shaped pupil.

Although widespread and abundant, Vine Snakes are rarely seen, relying on their incredible camouflage to avoid detection. These snakes can sit motionless for hours in a bush or tree, waiting for prey to come past.

Prey includes lizards such as Agamas and chameleons as well as a variety of smaller snakes and frogs. They are especially fond of eating the harmless green snakes in the genus Philothamnus. The bright red tongue may be waved around slowly to attract the attention of passing lizards (which probably confuse it for a worm) drawing them closer until they are within striking range. They rarely eat adult birds.

If harassed, these snakes may massively inflate the throat region as a warning gesture and are likely to strike out at this stage. The vine snakes may be confused with young Boomslang, which have similar colours in their juvenile phase. The young Boomslang has a more rounded head and massive emerald-green eye.

Vine Snakes have a slow-acting haemotoxic venom, very similar to Boomslang venom, but not as potent. Bite victims start haemorrhaging in the body, with blood moving under the skin, dripping out of the nose and mouth and internal bleeding from organs and through the urine. There is no antivenom for this snake and bites are treated symptomatically – usually with blood transfusions or clotting management. We have never had a death in southern Africa from a bite from this snake, however bites from larger species in East Africa have resulted in fatalities. Bites are very rare as this snake is docile and avoids humans. Most bites have been to snake catchers. Below are a few recorded bites:

The first death recorded by a vine snake bite was in 1953. At this time Vine Snakes were considered harmless and many snake catchers would free handle them. Mr Lock, 35, was a game ranger in Tanzania (still known as Tanganyika back then) who had a special interest in snakes and published some work on the snakes of Tanganyika. He was bitten by one of his Vine Snakes (reported as a Forest Vine Snake – Thelotornis kirtlandii, but more likely an Eastern Vine Snake – Thelotornis mossambicanus – given the location) in his collection after showing the snake to some guests. At the time, it was believed that Vine Snakes were harmless, and Mr Lock didn’t think much of the bite. The next day he started getting ill – headache, diarrhoea, stomach pains and vomiting – but assumed it was from drinking too much the night before. By the second day he started vomiting blood and was taken to hospital. The treating doctor had worked on a gastric ulcer on Mr. Lock two years before and assumed that was the cause of the symptoms. Mr. Lock did not mention the snake bite to the doctor as he was sure it was a harmless snake. Later that night Mr. Lock fell into a coma following violent convulsions and eventually passed away in the early hours of the following morning, 52 hours after being bitten.

The postmortem revealed haemorrhaging in the stomach, spinal fluid and bladder. The patient had kidney (renal) failure and was not passing urine. There was also blood oozing from the mouth and nose, and extensive brain haemorrhaging which likely caused the death.

In 1957, the late Dr Broadley was bitten by a large Oates’ Vine Snake (Thelotornis capensis oatesii) in southern Zimbabwe. The snake chewed on his finger whilst he climbed down the tree and managed to unlatch the snake from his hand and bag it. He noted swelling in the finger and there was blood oozing from the bite marks. By that evening he started oozing blood from scratches on his legs (from climbing the thorn tree) and shaving cuts. By the following day he was still bleeding from the cuts on his legs “The blood was very slow to clot, and I left pools of blood wherever I went”. The bleeding stopped on the third day and the swelling of the hand reduced by the fifth day, and he recovered fully.

Dr Blaylock also received a bite by Oates’ Vine Snake (Thelotornis capensis oatesii) in 1959 in Kariba, Zimbabwe. The snake latched onto the base of a finger and chewed for around 30 seconds before being removed. A headache developed within 30 mins and some swelling on the hand. He injected 5 cc polyvalent antivenom in the hand and 10 cc into the buttocks. None of the antivenoms have been shown to have any effect on the venom of the Vine Snake. Dr Blaylock felt sick and feverish, and started vomiting later that evening. The vomiting continued the next morning, and he was taken to hospital and given a blood transfusion. That evening he started bleeding from cuts and vomited more. He started developing blood blisters on cuts and had painful kidneys and stomach. The injection in the buttocks formed a haemorrhage that took two weeks to subside. Four days after the bite, blood clotting was satisfactory, and the patient was sent home. He still passed some blood in the urine on the fifth day but was fit within a week.

Another case in southern Malawi in 1965 was to a 30-year-old male who attempted to catch the snake. The bite resulted in blood oozing from the bite site, small cuts on the hand and out of the mouth. He received two vials of polyvalent antivenom initially (which is ineffective for Vine Snakes) and more when he reached the next hospital plus Vitamin K (which is also ineffective). He developed a patch of clotted blood under the chest muscle and was given two units of blood. His condition deteriorated over the next six days, and he received another six units of blood. Finally on the seventh day he stopped bleeding and started recovering well.

Another death was recorded in 1978 in a private collection in Germany. The eighty-four-year-old patient spent 18 days in hospital before succumbing to renal failure, swelling of the tissue of the lungs and haemorrhaging. It is uncertain of the exact species but is likely to be the Eastern Vine Snake (T. mossambicanus) or the Forest Vine Snake (T. kirtlandii).

A 13-year-old boy was bitten in Durban in 1980. He received 400ml blood transfusion and showed slowed clotting but no bleeding. He had two episodes of convulsions and a tight chest. He was examined for six days in hospital but was discharged when the platelet levels had returned to normal.

Thelotornis capensis oatesii – 1987 – 41-year-old bitten on the wrist whilst moving a vine snake. Bled for the first 30 minutes. Had a headache and started bleeding from old scratches. He was hospitalised and by the next day still oozing blood plus a swollen wrist. Vitamin K injection in the shoulder, which was bruised and oozing blood. He received 6 units of blood on arrival at the hospital and 6 units 4 hours later and again 24 hours later. Bleeding from small wounds stopped after 3-4 days and swelling of the wrist subsided and he was discharged.

A 2003 report of a bite to a dog (8kg pug) by the Southern Vine Snake (Thelotornis capensis capensis) resulted in a nosebleed for four days. No other symptoms were recorded, and the dog made a full recovery.

Treatment is generally done with blood platelet transfusions and supporting the kidneys. None of the antivenoms produced show any effect against the venom of the vine snakes. Vitamin K injections are not advised. Naturally, vitamin K assists the body with producing clotting factors in the liver. The problem in haemotoxic bites is that it doesn’t matter how much the liver produces, the body uses it all for other processes whilst in shock. Additionally, injections can also cause haemorrhaging in the tissue which is problematic and not ideal during these bites.

Despite being highly venomous snakes, the vine snakes are placid and can be observed from a few meters away in a safe manner. The camouflage is easily appreciated whilst watching this snake as your eyes struggle to identify the body from surrounding branches and twigs. Although a placid snake, it must be treated with caution and bites avoided at all costs. In a case of serious envenomation from this snake there is no guaranteed treatment.

—————————————————–

Johan Marais, the leading herpetologist in South Africa and owner of the African Snakebite Institute, contributed this article to our website. His details can be found on the following link.

Further readings about Snakes of Southern Africa on this website:

About snake home ranges and territories

Snake Season in Southern Africa

Preventing Snakebite in Southern Africa

Field dressing and cooking a puff adder

Top ten rare snakes of Southern Africa

Small black snakes of Southern Africa

Traditional Remedies for Snakebite

.