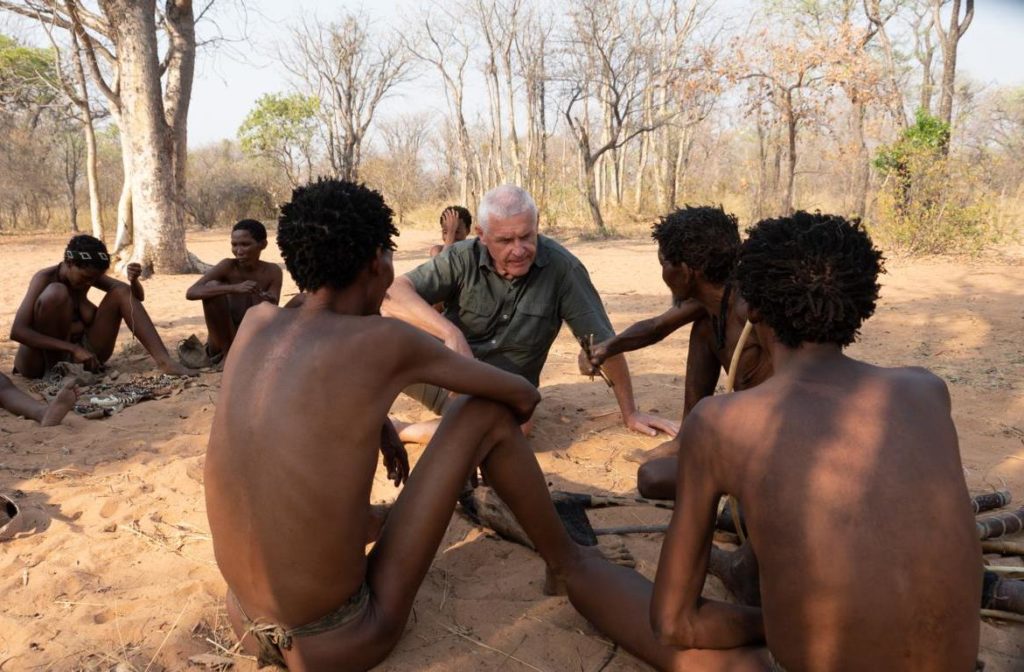

Generally speaking, the Khoi-san (‘Bushmen’) employ bows and poisoned arrows for “tracking and stalking” during hunting in Northern Namibia and North-Western Botswana. The various Khoi-san tribes utilize different materials and techniques for crafting these weapons. However, in this article, we will focus solely on the bows of the Ju//hoansi Khoi-san people (formerly known as !Kung).

Parts of a Khoi-san hunting bow

A Khoi-san bow comprises several parts, including the stave, the string, string stops, and materials for preserving the bow’s elasticity.

Bow stave

The bow stave is typically round in cross-section and tapers at both ends. The preferred wood for the stave is White Raisin Bush (Grewia Bicolor). The Khoi-san do not use fronds of iLala palms (Hyphaene coriacea) for their bows, but neighboring Ovambo tribes do. The bow arms are often reinforced by wrapping them with animal sinews, ligaments, or leather strips at various points.

The length of the bow varies depending on the target game, shooting range, family group tradition, and the available materials. The average size of a bow is between 98-115 cm (3.2-3.8 ft). Short bows of approximately 69 cm (2.3 ft) are used for hunting small birds like quails and francolins. The longest bows, used by Northern Khoi-san tribes, can reach up to 150 cm (4.9 ft) in length. The typical brace height of the bows is around 20 cm (approximately 8 inches).

Once the stave material has been cut to the correct length, it is hewn on both ends to the required tapered dimensions using a multi-tool that can be used as an adze and a chopping tool. Interestingly, this tool can also be used as a pipe for smoking tobacco.

After shaping the stave, it is debarked using a knife blade turned 90 degrees to the stave. This process involves scraping the bark rather than cutting it to avoid removing any outer wooden cells along the round cross-section that could compromise the bow’s strength.

String stops

The bowstring is typically fixed on one end of the stave using a simple sling and on the other end by multiple wraps. However, before attaching the string, both ends of the bow stave must be prepared for these attachments. The bushmen do not cut into the stave wood but reinforce the stave ends and add the cord stop.

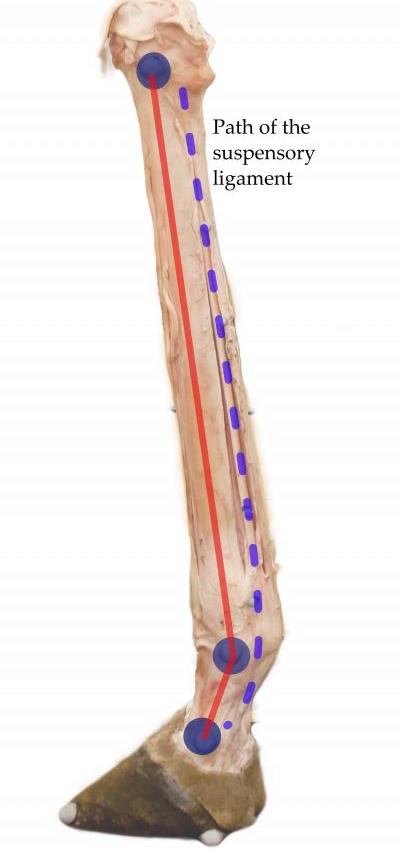

An adhesive is applied at the end of the stave where the sling is attached, and then a layer of separated strings of giraffe suspensory ligament is covered with this adhesive. The string stop is just a slight increase in the thickness of this ligament string on the stave.

Two more details to consider are the adhesive used to glue the ligament to the stave and the ligament itself.

The adhesives used on the stave

Khoi-san people commonly use two natural adhesives for bow assembly: Sweet thorn acacia (Vachellia karoo) resin and sap from Commiphora species.

Sweet thorn acacia resin is collected by cutting the trunk and allowing the sap to ooze out and harden in the air. This resin is white-yellowish-reddish and looks similar to “Arabic gum.” It is heated and applied to the bow, and it will re-harden again.

In our case, black resin was used: Commiphora sap boiled and mixed with fine charcoal. This addition thickens the adhesive and improves its holding strength.

The most famous Commiphora resin is extracted from Commiphora africana, the African Myrrh. It is often used in cosmetics and, therefore, valuable for generating cash. Other Commiphora species found in the area include:

- C. crenatifolia (Dune cordwood),

- C. gariepina (Gariep cordwood),

- C. kraeuseliana (Mountain cordwood),

- C. mossambicensis (Mozambique corkwood), and

- C. pyracanthoides (Firethorn cordwood).

Sap from all of these species can be used to produce adhesives to glue ligaments onto the stave. The boiled and ready-mixed glue is smeared onto a small stick and rubbed onto the stave.

Strings of giraffe ligament

Khoi-san people in Southern Africa and the Hadza people in Tanzania use giraffe leg suspensory ligaments to bind their bow staves.

Fully grown giraffes weigh around 1000 kg (2200 lbs). As a result, each leg has to support at least 250 kilograms of weight constantly. Due to their long and thin legs, giraffes need solid bones and suspensory ligaments in these areas. This is why bushmen prefer the outer layers of the fused metatarsal and metacarpal bones, also known as giraffe cannon bones, for arrow parts. The suspensory ligament from the giraffe legs is also the preferred binding material for the bow staves.

I want to stress that these strings are not sinews but ligaments specific to giraffes. See this article. Although in nearly every literature about bushmen and even in museums, this suspensory ligament is called ‘sinew’. However, this suspensory ligament has particular characteristics. One is its length, stringiness, and uniform thickness. It is situated within a channel in the bones. When dry, it can be separated into very thin, long strings. When wetting these strings, they become immediately soft and stick to each other like glue. This adhesion action can be made permanent when heating up moderately. After hardening, these ligament strings become colorless.

In modern times, Khoi-san people rarely shoot giraffes. As a result, game farmers in Northern Namibia typically provide the metatarsals and metacarpals of hunted or preyed upon giraffes to Khoi-san communities. When Khoi-san themselves shoot a giraffe, the first step in butchering is to remove the four cannon bones for immediate processing, even before gutting the animal. This demonstrates the high value that these bones and ligaments hold for them.

Wrapping of giraffe ligament

The ligament strings are dried and then rehydrated in water before use. Thin strips of ligament are plucked out and used for binding. These wet ligament strings are wound around the adhesive layer at the stave end, where the string sling is attached. Spitting them during wrapping is essential to keeping the ligament strings wet.

The same black adhesive described before will be applied at the end of the stave, where the string will be wrapped. The wet giraffe ligament string is wrapped around this area, with a short twig bound into the wrapping. This twig serves as a cord stop and helps to jam the string end after stringing the bow with the correct tension.

After wrapping, the wet giraffe ligament string is slowly dried over a small piece of glowing coal. It is crucial to toast the wrapping just enough to fully dry it without burning it. This causes the wrapping to shrink and securely binds all parts together.

Bowstring

The traditional bowstrings used for Khoi-san bows were made from Steenbuck (Raphicerus campestris) bellies or finely twisted leather strips of Kudus (Tragelaphus strepsiceros) sinews. The two backstrap sinews of a fully grown Kudu can be up to 1.2 meters long. These ligaments are split into single strings that can be twisted to form a long and combined string. Two of these combined strings are twisted opposite to the single-string twisting direction to manufacture the traditional bowstring.

In the early 20th century, bushmen learned from neighboring Bantu tribes to use plant fibers from Sanseviera species. Since then, these plant fibers have nearly completely replaced all other animal-based string materials they use.

Kudu sinews and leather strips are non-elastic string materials. After shooting, these animal-based strings immediately absorb most of the remaining energy in the bow arms, putting a significant strain on them. On the other hand, plant fibers are more elastic and can absorb some of the power, reducing the strain on the bow. We described it in this article since making bowstrings from Sansevieria plant species requires a detailed explanation.

Maintenance materials

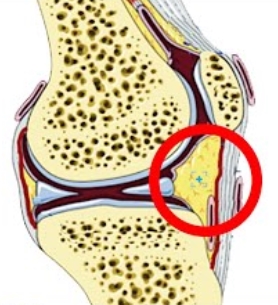

The wood must be regularly lubricated to maintain the bow’s elasticity and avoid crack formation. For this purpose, the fat pad under the kneecap of large antelopes or Zebras is used. If a bow curves too much, bone marrow is applied to straighten the stave up again. Bowstrings of twirled pieces of skin or sinew are rubbed with bone marrow at regular intervals to ensure continued elasticity. On the other hand, plant fiber strings are coated with beeswax.

Lessons learned about bushmen bows for hunting:

- The average length of bushmen bows for hunting mammals is around 1.1 meters (3.6 feet). A brace height of approximately 20 centimeters (8 inches) is most common.

- The preferred bow wood comes from Raisin bush species, especially Grewia bicolor.

- Cord stops on both stave ends are made from corkwood (Commiphora sp.) sap and strings of giraffe ligaments.

- Traditionally, bushmen used Kudu backstrap sinews for the string, but nowadays, Sanseviera plant fibers are mainly utilized.

.