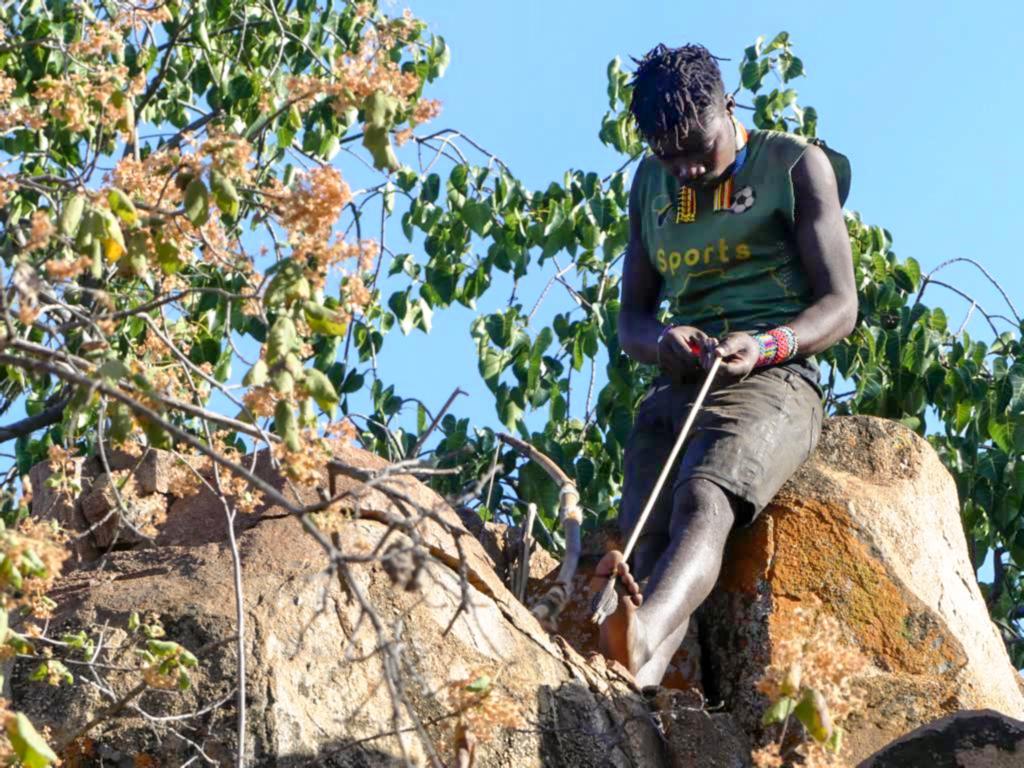

Arrow shafts are a piece of Hadza men’s identity. Remotely living Hadza men always carry their bows, arrows, and firesticks. Whenever they have leisure time, they attend to their arrows by building new ones, checking and correcting their straightness, or improving their wooden tips.

Principle arrow design

Hadza arrows are just one piece of a wooden stick with a tip on one end and a nock and fletchings on the other. At three types of arrows, the tip will not detach when hitting an animal. These are wooden tips, lance-shaped iron arrowheads, and blunt arrowheads. Only the barbed iron arrowheads with poison are designed to break away from the shaft after lodging into the animal’s body.

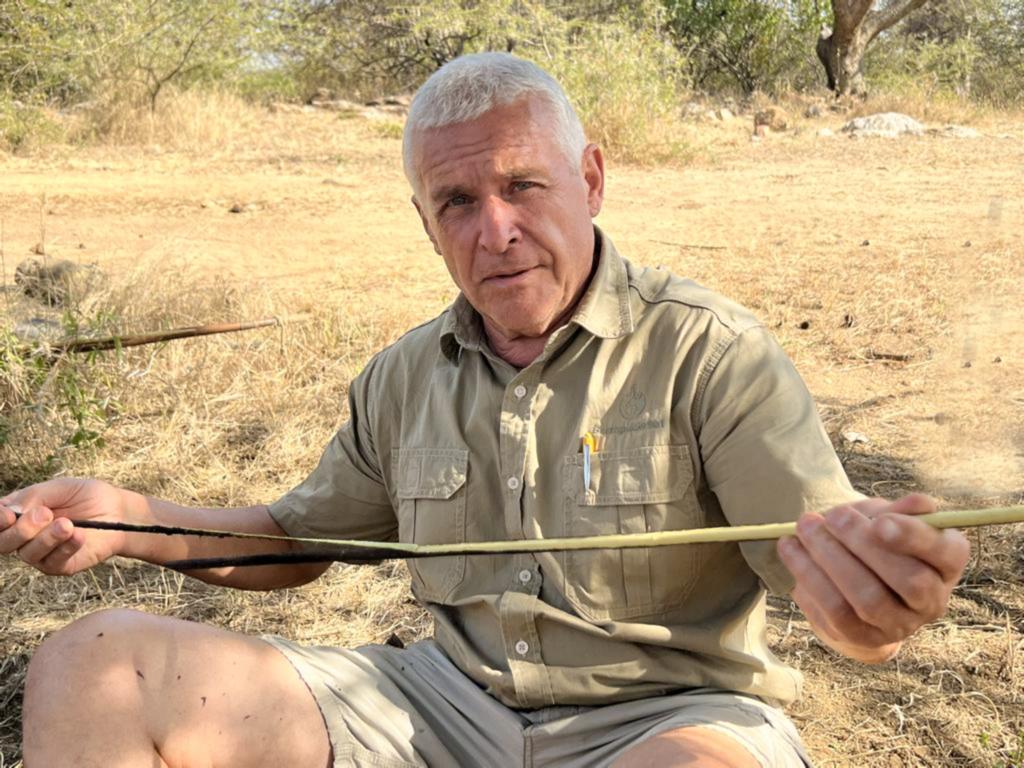

Even these barbed arrowheads are designed crudely. They function by pulling out the wooden shaft from the conical lower end of the iron arrowhead when the hit animal is bolting. There is no comparison with the sophisticated arrow design of Khoi-san bushmen around the Kalahari, which uses a design consisting of three parts instead of two. I described the Khoi-san Bushmen arrow design in more detail in this article on my webpage.

The length of the Hadza arrows is generally around 92cm / 3ft, depending on the hunter’s strength, bow draw weight, string length, and brace height. The wooden shaft of the arrows has a uniform diameter between 7.5–8mm / 0.29–0.31’’.

Which wood is used for Hadza arrow shafts?

Four species of wood are commonly used for arrow shafts. These are:

- Mutateki, River Dombeya (Dombeya kirkii). This shrub or tree is a favorite for bow-making, and young shoots are also used as arrows.

- Kongoroko, White Raisin bush (Grewia bicolor). This shrub is ubiquitous throughout the whole area of Yaeda South, and its shoots are perfect in size and hardness for all types of arrows.

- Tlehako, Sacleuxia (Sacleuxia newii). That is the favorite wood for poisoned barbed iron arrowheads.

- Embereko, Warty Donkey-berry (Grewia forbesii). It is a replacement wood if the other three wood species are unavailable.

Heating and debarking

After the green shoots are cut from the bushes, they are still processed into arrows on the same day. As a first step, a fire is lit, and the sticks are heated along their entire length.

The fire will just slightly char the outside of the bark but will boil the plant juices inside. This way, steam erupts inside and loosens the bark from the wood. The bark can, therefore, be stripped of the wood easily and in long stripes.

Smoothing of knots

After debarking, the sticks will be placed between the bowyer’s toes and his breast. This position acts as a vice, allowing the stick to rotate while still providing steady support for the carving. That way, all knots and protrusions on the wood surface can be easily removed with a knife.

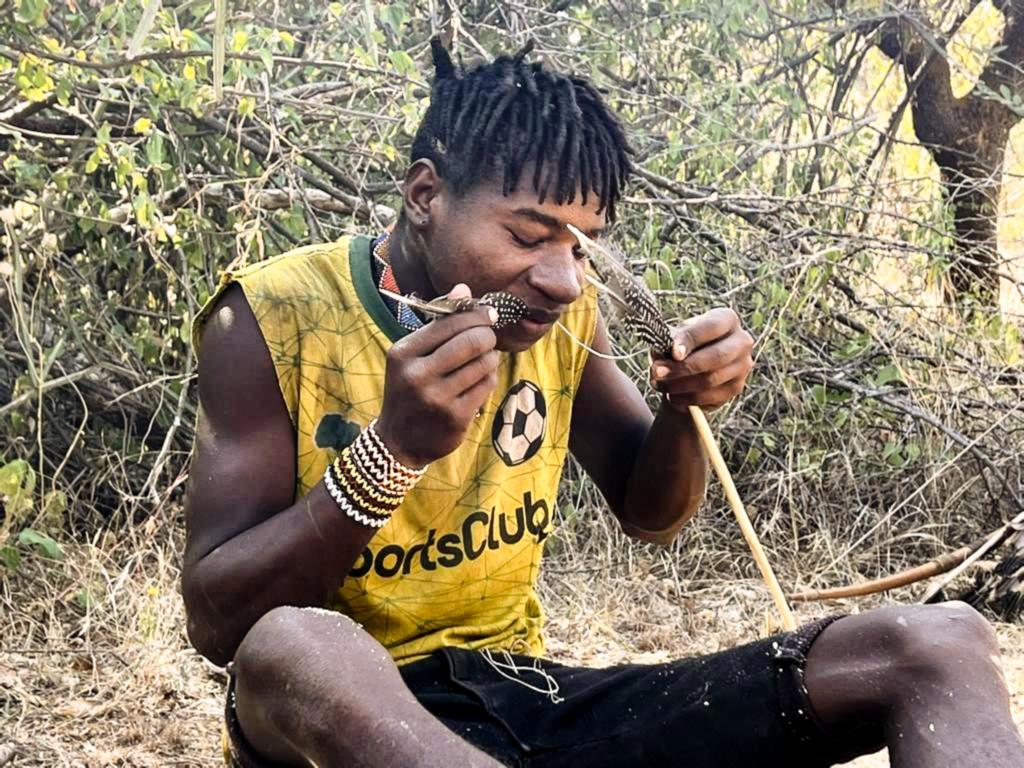

Bending with the teeth

The Hadzabe’s unique way of straightening arrow shafts is to bend them between the teeth. This method works best if the wood is still warm and juicy. Therefore, the shafts are repeatedly reheated in the fire at the required spots for easier bending.

Cutting the nock

Finally, before fletching, the nock will be cut into the rear end of the shaft. It is cut 5–7mm / 0.19-0.27’’ deep and shaped like a slight V-slot. The bottom of the slot is about 2.5mm / 0.10’’ wide and about 3mm / 0.12’’ on the entry.

Fletching the arrow shafts

The purpose of fletching on the back of an arrow is to create drag on the back end of the arrow. If the back of the arrow moves slower than the front end, the arrow will fly straight. Therefore, various alternative materials can slow down the rear end. However, feathers for this function are the best, as they will not interfere when passing the string during the shot. Additionally, they are waterproof, and if vanes are used, they minimize drag.

Feathers of which birds are used for fletching?

The Hadza people use either split or unsplit feathers on the arrow shafts. During our stay with the Hadzabe, I checked the origin of the feathers they were using and found them to be of bird species, as shown in the following.

Whole (unsplit) feathers

Hadzabe people use medium-sized and not-too-stiff feathers as a whole. They do not split these feathers in the middle. Feathers of two different bird species were found, which were from ground birds of small to medium size.

Helmeted Guineafowl (Numida meleagris)

Grey-breasted spurfowl (Pternistis rufopictus)

Split feathers (vanes)

If the useable parts of feathers become too stiff, they are split in the middle so that two vanes can be cut from them. Feathers of the following species were found.

White-backed vulture (Gyps africanus). Those feathers are often found at places where vultures were scavenging/feeding. They heavily flap their wings at these places to ward off intruders and loose wing feathers on that occasion, which will then be collected by the Hadzabe.

Von der Decken’s Hornbill (Tockus deckeni). This hornbill species abounds in the remote Hadza areas and is often shot on their favorite fruit trees, to which they will return regularly.

Helmeted Guineafowl (Numida meleagris). This well-known species likes to take sand baths, where they lose fleas and feathers. They are the favorite target of Hadzabe hunters, who are looking out for fletching feathers. Guineafowls mainly consist of feathers, guts, and bones; there is little meat on them.

There is a mix of Guineafowl and Von der Decken’s Hornbill feathers. Hadza hunters even mix feathers of different bird species.

These are either the primary wing feathers of a Southern Ground Hornbill (Bucorvus leadbeateri), or the undertail coverts of a Von der Decken’s Hornbill.

These could be the side feathers of an Eastern Chanting Goshawk (Melierax poliopterus).

In summary, Hadza people seem to use feathers of all bird species, which have the required stiffness to be used as a whole or split in half. Feather color seems not to be as crucial as the barbs’ stiffness. The colors are anything from black to brown to white. The barb stiffness ranges from soft scapular feathers on spurfowls’ backs to vultures’ stiff primaries.

Attaching feathers to the arrow shafts in Hadzabe style

Hadza people have a unique style of attaching the fletching on arrow shafts. For fixation, they need dry Impala- or Kudu ligaments for binding. These ligaments will be split into thin strings, chewed, and wetted in the mouth.

The wet ligament is then kept under tension by the mouth, and the feather tips are wrapped on the back end of the arrow shaft.

Four feathers are attached at their tip to the shaft so that the nock slot stays in line with the feather rachis.

After that, the feathers will be shortened, bent over to the front end of the shaft, and securely bound with ligament.

For demonstration purposes of the bindings, see the following untidy fletching, which is missing one feather.

The same binding system is also applied to split feathers (vanes). The difference is that five vanes are bound onto the shaft instead of four whole feathers. And like all fletchings, the split rachis must be cut or ground to a size that can tightly hug the shaft.

One more topic has to be mentioned: During our stay with the Hadzabe people, we did not see any vanes or feathers glued onto the shafts. The Hadza clan we met never used any glue, only locked down feathers and vanes mechanically with ligaments.

Lessons learned from Hadzabe arrow shafts and fletching:

- Four species of wood are used for arrows.

- Arrow shafts will be debarked, shaved, and straightened.

- Feathers from a variety of birds are used.

- Depending on rachis- and barb stiffness, feathers will be used as a whole or split in half.

- Feathers or vanes are bound with ligament on their tip at the back end of the arrow shafts.

- After that, feathers or vanes are bent over and bound to the shaft.

Additional information

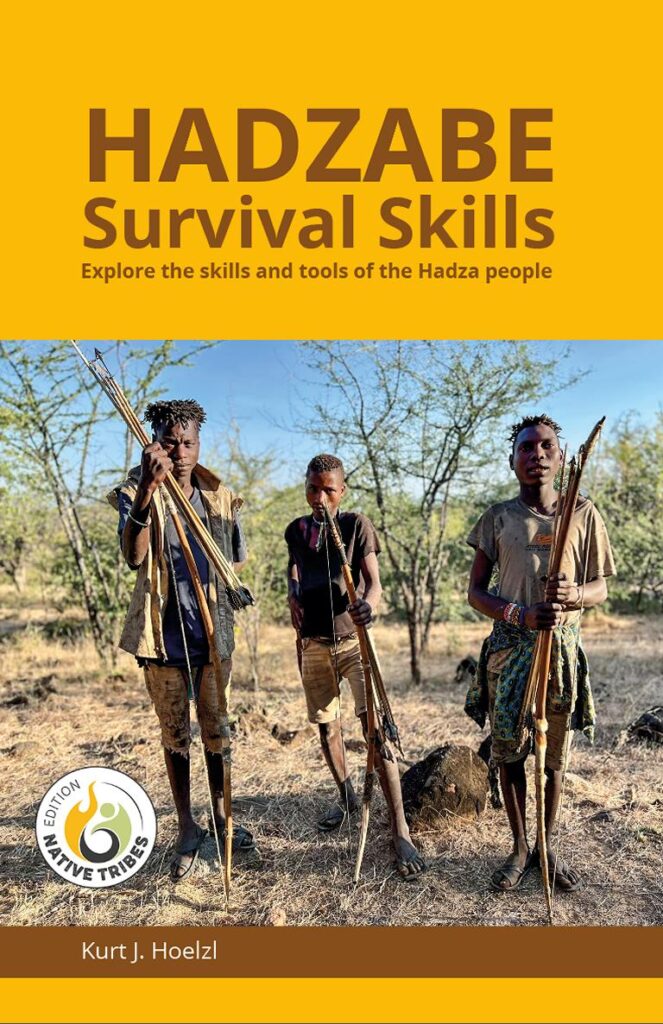

My book ‘Hadzabe Survival Skills‘ offers more skills, knowledge, tools, and techniques for the Hadzabe people’s life in their natural environment. It is available on Amazon.com and Amazon’s regional websites.

.

2 comments

Kurt Hoelzl

Hi Will,

The cupped surface of the feather—in the middle of the feather’s length —will face out of the shaft. You can see this clearly in the Eastern Chanting Goshawk photo in the article. Not only do the Hadza people use this style, but Datogas do as well. Datogas bind an additional wrapping of sinew in the middle of the feather’s length to hold this outward cupping down.

I’m a bit hesitant to either call it convex or concave, as this definitions depend on the perspective the observer takes – either from or to the shaft-side.

Will K.

When the whole small feathers are bound to the shaft with sinew, does the convex or concave side of the feather face the arrow shaft (in other words, does the cupped surface of the feather face out or in, toward the shaft?)?