At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, many draught animals were released in the wild in Western Australia, as motor vehicles took over their work. These included donkeys and camels. Both species flourished thereafter in the wild and formed huge herds, to the detriment of many farmers. Most of these animals were culled within the last decades through eradication programs. However, when we visited the Kimberley region of Western Australia at the end of 2024, we still came across two herds of feral donkeys. Following their trails would have helped us find water in a survival situation.

Feral donkey behavior

Feral donkeys form two kinds of herds: breeding herd or bachelor herd. Breeding herds consist of the dominant stallion with three or four mares and their offspring. Moreover, like in Zebra herds, the dominant stallion accepts one or two young stallions for better herd protection. In droughts, these family- and bachelor herds often assemble with other herds, which can be up to 500 heads strong.

Feral donkeys will drink twice daily from surface water sources. If no surface water is available, they will dig deep holes with their hooves in dry river sand in search of water. They will dig a string of wells if there is a big herd. Feral donkeys, however, are well known for defending their water sources viciously. Like Zebras – again – feral donkeys are very specific about water quality, which has to be clean. Therefore, as a general rule, it can be stated that water, which feral donkeys drink, can also be drunk by humans.

Feral donkey trails leading to water.

In the morning and evening, the donkeys always move on the same trails to the water, forming deep ruts on these trails. When finding such ruts, we must follow in the right direction, towards the water, not away from it. Sometimes, the lay of the land or visible differences in vegetation will ease this task, for example, when the trail leads from a higher to a lower elevation, or when greener plants are visible. However, an undulated landscape often makes the task more difficult. In such a case, two signs have to be observed. These are Y-trails and the direction of hoof prints.

Y-trails

I already described these trails in one of my former articles, ‘Game trails towards water in African savannas’ . There, I was writing: ‘…Seeing a trail with the tracks of grazers, not only the direction of where the hooves are pointing, is important, but the confluence with other mixed game trails is also essential. These merging trails form typical Y-shapes, from which the single resulting trail leads toward the water. In a typical flat savannah country, single waterholes or linear water lines (sandy creeks) with only specific access points will provide the life-saving liquid. Therefore, all game trails will converge towards these places with water. …’

In summary, when two trails converge to one, the water can be found in the direction of the one remaining trail.

Direction of hoof prints

If no converging trails can be found, the hoof prints must be scrutinized and related to the time of day. If all fresh tracks point in one direction and it is early morning or late afternoon, the problem is solved. The donkeys went to the watering hole. Later, they will return to the bush again, and their fresh tracks will overlay the tracks towards the water.

Therefore, correlating track age and direction with the anticipated behavior of the donkeys is of paramount importance, which, however, can deviate from their actual behavior in some cases., So, it is not 100% foolproof, and the tracks and surrounding environment have to be judged anew constantly.

Donkey tracks

Donkeys are like horses, odd-toed ungulates, and their tracks are easy to determine. They prefer to move one behind the other and leave distinctive trails and ruts behind. On the other hand, feral horses (Brumbies) run all over the place and leave their tracks, but no distinctive trails.

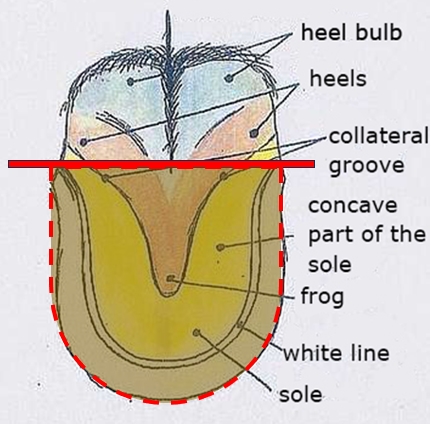

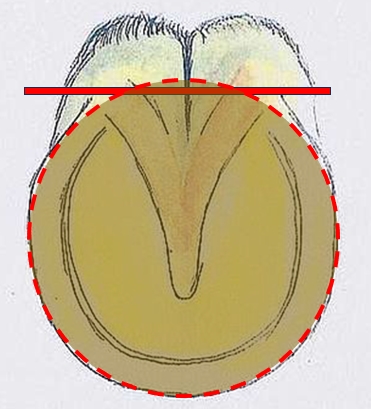

Secondly, each donkey hoof track is slim and U-shaped, whereas horses show a round footprint. Moreover, the heel in donkey tracks pictures far behind the hoof wall.

The horse’s heel is very close to the end of the hoof wall. Many other distinctive differences exist, but these two features are enough to determine a feral donkey track securely.

With these hints of track pictures and trail specifics, it will be possible to find a surface water source that feral donkeys use that is fit for humans to drink. We hope the government will not eradicate the remaining feral donkeys in the Kimberleys. As Kanchana Station proved, feral donkeys help prevent wildfires and foster re-vegetation, and by digging water wells, they benefit other wildlife.

Lessons learned about feral donkey trails leading to water:

- The number of feral donkeys in Western Australia is steadily declining.

- In case of emergencies, donkey trails will lead towards water.

- Y-trails and the direction of hoof prints will determine the direction to follow.

- Donkey tracks show a U-shaped, slim hoof and a heel far behind the hoof wall.

.