Snakebite was recently recognized as a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization with about 20,000 snakebite fatalities reported every year in Africa. Subsequent morbidity affects far more people than that. In South Africa we have around 4 000 snakebites a year with less than 1 000 people hospitalized, and around 10 – 12 fatalities. Treating serious snakebites is complex, often requires antivenom and many victims require surgery. A single snakebite can cost anything from R 100 000 to R 1 000 000 (about 5,000 – 50,000 USD as of Aug. 2023) to treat.

Many snakebites are from mildly venomous snakes, such as this Tiger Snake, and are not a medical emergency. Image © Luke Kemp.

General information

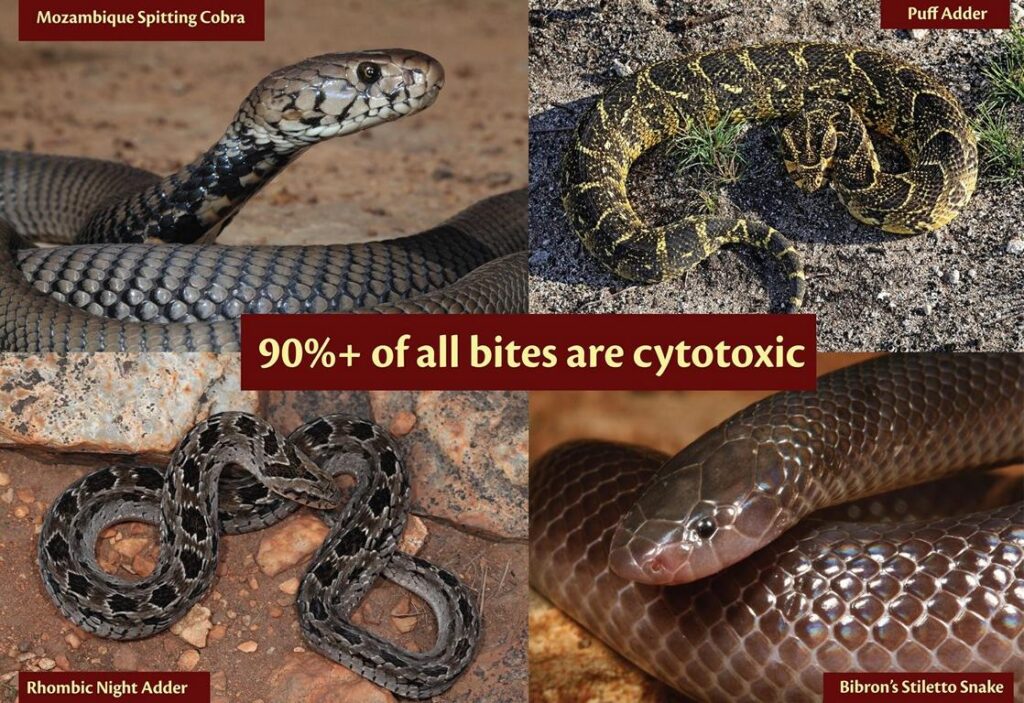

There are many ways in which one can reduce the chances of being bitten by a snake. Most victims are bitten in the early hours of the evening, largely in summer between November and April and when accidentally standing on them. By using a torch at night and sticking to pathways, one can greatly reduce the chances of being bitten by a snake. More than 90% of all snakebites in Southern Africa are inflicted by four snake species – the Mozambique Spitting Cobra, Puff Adder, Bibron’s Stiletto Snake and Rhombic Night Adder. The venom of these snakes is largely cytotoxic, causing pain, swelling and possibly tissue damage. Fatalities from Mozambique Spitting Cobra and Puff Adder bites are rare and there have been no deaths reported from bites of the Bibron’s Stiletto Snake and Rhombic Night Adder in Southern Africa.

Mozambique Spitting Cobra bites

The Mozambique Spitting Cobra is a problematic snake. This snake is abundant where it occurs, is an active hunter, especially in the early evening and often accidentally ends up in people’s houses. Once inside, the snake will continue to hunt and often bites people while asleep in their beds. Having investigated many such cases it is evident that the snake is not seeking heat or accidentally being rolled over onto.

These snakes are smelling a sleeping mammal and mistaking humans for a meal. Most bites are typical feeding bites with severe envenomation and results in most victims being bitten in the face or on hands and arms. Preventing such bites would involve properly sealing off all exit doors – if the gap under the door is big enough to push a finger through, it is big enough for a Mozambique Spitting Cobra to enter. Never sleep with sliding doors open and if you wish to do so, install mosquito-proof doors. People in rural areas are encouraged to sleep under mosquito nets.

Mozambique Spitting Cobras are ferocious feeders, eating anything they can fit in their mouths. Image © African Snakebite Institute

Puff Adder bites

Puff Adders are very common and widespread and move largely at night. Using a torch and sticking to roads, sidewalks and paths will go a long way to prevent Puff Adder bites. Although they are well camouflaged, it appears that bites largely occur from snakes that are basking or are on the move. At this stage, the snake is vulnerable and will be defensive. A Puff Adder in ambush mode lying in leaf-litter is very reluctant to bite. This was tested by Wits University and a publication will follow in the near future.

One hour after a Puff Adder bite showing the start of swelling and discoloration. Image © Marius Burger.

Bibron’s Stiletto Snake bites

Bibron’s Stiletto Snake is fossorial and spends most of its life underground but emerges on hot summer nights especially after rain. It is a brown to blackish snake with small eyes and people often mistake it for a harmless snake, pick it up and then get bitten. Others are bitten when rescuing a stiletto snake from a swimming pool or even taking one away from a cat. These snakes have large fangs that protrude from the sides of the mouth, even when closed, and therefore cannot be handled safely in any way. Never pick up snakes and never try to grab any snake behind the head.

Bites from Stiletto Snakes are not life-threatening but very often lead to amputation of the limb. Image © Myke Clarkson.

Rhombic Night Adder bites

Rhombic Night Adders, despite their common name, are more active in the day and bites occur largely when one is accidentally stood on. The venom of this snake is often underestimated and although not potentially deadly, it is potent enough for a child to end up in hospital. Stick to footpaths and wear shoes when in the bush. Also watch your hands when collecting firewood or moving pots and garden refuge.

General recommendation to prevent snake bites

Around 85% of all snakebites are inflicted below the knee when people accidentally stand on snakes. If you are going on hikes or have to be in the bush, wear leather boots and long trousers. Stick to foot paths and be careful where you put your hands, especially when climbing mountains. Snake gaiters are a good idea but make sure they are tested for snakebite and comfortable.

Never attempt to catch or kill a snake. We often see people trying to catch a snake with braai tongs. They are not designed for snake catching and are too short for most snakes. Killing snakes may put you in the danger zone and increase the chances of getting bitten. Using a firearm to kill a snake is dangerous with the possibility of bullets ricocheting or doing a great deal of damage. If you often encounter snakes and wish to safely remove them, consider doing an African Snakebite Institute Snake Awareness, first aid for snakebite and venomous snake handling course.

We teach people how to safely remove snakes using the correct equipment in a safe manner for both the remover and the snake. Additionally, you can use the free ASI SNAKES app to find a snake remover in your area and get the animal safely removed and released elsewhere. There are over 700 snake removers on the African Snakebite Institute free app, ASI Snakes. Go to http://bit.ly/snakebiteapp to download the app, then go to Snake Removal and the app will list the snake removers in your area with their mobile number.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Text of this article © African Snakebite Institute. The professional background and contact information of the author of this article, Johan Marais, can be found here.

Further readings about Snakes of Southern Africa on this website:

About snake home ranges and territories

Snake Season in Southern Africa

Field dressing and cooking a puff adder

Top ten rare snakes of Southern Africa

Small black snakes of Southern Africa

Traditional Remedies for Snakebite

.