If you are outdoors in boreal forest biomes worldwide, protecting yourself against wind and wetness is paramount. And to light a fire for warmth. The necessary firewood should be dry to burn hotter and with less smoke. But if you are out in the woods, how do you know if your firewood is sufficiently dry?

Moisture testing methods

Literature, see this link, proposes four different methods of determining whether firewood is recommendable for lighting a fire. These are:

- Soap test

- Sound test

- Look at the features of the wood piece.

- Moisture meter

I do not want to comment on the soap test and moisture meter method, as both are unsuitable in the forest. The sound test is also not recommendable, as the resulting amplitude and frequency of the sound depend on too many different parameters. Only carefully examining the features of a piece of wood and its growing surroundings will help determine if it is suitable as firewood. The ‘Dead, Dry and Standing’ guideline should be applied as a standard routine.

And there is one more test for firewood, which is virtually unknown in Western circles. This test is used in the Russian Taiga, where many people regularly move into the forests for fishing, hunting, mushroom collection, berry picking, or trapping. Before they light a fire, they check the firewood by holding the freshly cut edge of the wood to their lips. If it feels cold – it’s wet; if it feels warmer – it’s dry. Additionally, to this temperature sensing, they also smell the wood. Their olfactory memory and experience will help them judge if the wood is dry.

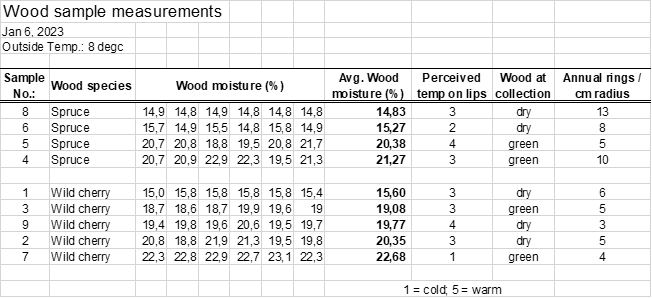

Moisture measurements on wood samples

I have now checked if this information from a Russian bushcrafter is correct or just a myth. I collected dry and green samples of spruce and wild cherry from the same trees and measured their moisture contents, tested the perceived temperature of the cut area on the lips, and counted the annual rings of the wood samples. Moisture measurements were done with a two-pin moisture meter.

Results of moisture measurements on the wood samples

- Every wood species should be considered separately.

- Spruce

- There were distinctive differences in moisture contents between green and dry wood samples.

- Dry samples feel tentatively warmer on the lips compared to green samples.

- A colder (higher moisture) ring could be felt at the dry samples on the outside surface.

- At high wood densities (many annual rings), the thermo-sensory impression moves towards a colder feeling.

- Wild cherry

- Showed an overlap of moisture contents amongst green and dry samples.

- The colder temperature throughout the sample could only be felt on the lips of the green sample with high moisture content.

- All dry samples were colder at the core and not on the outside.

- The temperature differences in various cut areas could be sensed on both wood species with closed lips.

Summary

Therefore, the Russian Taiga method of sensing moisture content with closed lips on freshly cut wood is suitable for determining dryness.

And I would restrict its suitability to coniferous trees under similar growing conditions only. The wood of deciduous trees can only be divided into ‘completely green’ and ‘somewhat dry.’ And as ‘completely green’ wood is evident, this method is more suited for coniferous trees. Therefore, feeling the temperature on the lips is very practical. It helps to determine if coniferous firewood is dry and should have its rightful place in all boreal forest biomes of the Northern Hemisphere.

Lessons learned about judging if firewood is either wet or dry:

- Four methods are established in Western countries for measuring moisture content in wood.

- Two of these methods are unsuitable for survivalists; one is partly suitable, and one is connected to logical thinking.

- There is one more method: holding the cut wood on the closed lips and feeling the temperature.

- This method is practical and suitable for coniferous tree woods under similar growing conditions.

.