Hadza bows are not only used for hunting but are also ubiquitous adornments for nearly all Hadza men. They even carry their bows, arrows, and firesticks around when they are not going to hunt. The bows are often short-lived and last between one month and one year. Hadza men, therefore, often can be seen whittling bows.

Wood for bow building

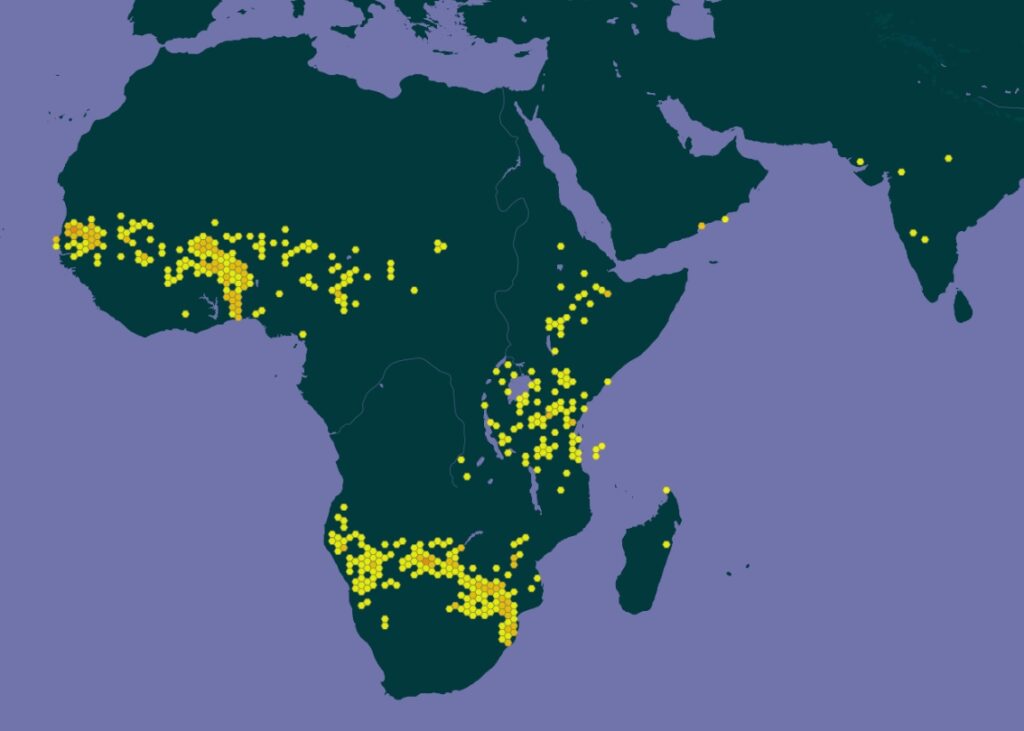

There are three species of wood that Hadzabe people use for building their bows. They call them Mutateko, Ts’apaleko and Kongoroko.

Mutateko

The best bows are built from this wood species: the ‘River Wild Pear’, also known as ‘River Dombeya’ (Dombeya kirkii). This large shrub is a Malvaecea and occurs along river lines and in rocky areas of Eastern Africa. A good description of this plant can be found under this link.

Ts’apaleko

If suitable Mutateko wood is unavailable, Sandpaper saucer-berry or Snot berry (Cordia monoica) can also be used as a bow wood. This Ts’apaleko shrub is very common in the Yaeda area. A plant description can be found here.

Kongoroko or Kongolo

The White Raisin bush (Grewia bicolor) is the most common plant of the three wood types. It occurs in many parts of Western-, Eastern-, and Southern Africa; a description can be found here.

White Raisin branches are often straight, and the wood is tough. Therefore, it is used not only for building bows but also for arrows, fire sticks, climbing pegs, and various other demanding applications.

Bow dimensions

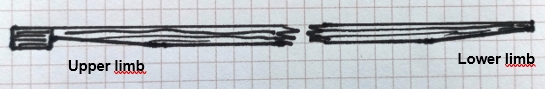

Hadza bows vary significantly in length and draw weights. We measured the length between string fixation points with an average of five bows measuring 153cm / 5ft. This is about 20cm / 7.8’’ longer than measured by Pontzer et al. here. The diameters at the midshaft were around 2.8cm / 1.1’’, and the brace heights were between 17-22cm / 6.7-8.7‘’. All bows we saw had a round cross-section, thinning out at both ends. They showed a bending handle, parallel limbs, and an elliptical tiller.

Pontzer H. et al. measured Hadza bows’ draw forces and reported a draw force of on average 311N / 70 lbf (lbf pound-force equals lbs ‘pounds’) +/- 98N / 22lbf for a net draw length of 55cm / 21.7’’. The draw weight of a basic-entry modern longbow is about 270N / 60lbf at 32’’ draw length.

I’m a bowhunter and have shot about 50 times with various Hadza bows. Based on that experience, I estimate these bows’ draw weights were between 60 and 90 pounds at full draw (55cm / 21.7’’), which correlates well with Pontzer’s measurements in 2017.

Building Hadza bows

Bow stick

Initial steps for carving a bow stick

After collecting a sufficient-sized, straight branch of one of the three mentioned wood species, the green bark will be removed by pulling it off the wood. Before that, the bowbuilder decides which end of the stick will be the lower limb and the backside of the finished bow. He will leave about 10cm / 4’’ of bark on the future upper limb side.

The stick will be trimmed to the approximate required length, about 10cm / 4’’ longer than the distance between both fingertips of the outstretched arms. The opposite end of the future lower limb will then be clamped between the toes, and the wooden material will be carefully scraped off towards the upper body with a knife. At this stage, the lower limb will already be shaped with a taper, keeping the wooden fibers of the backside intact.

After carving the lower limb, the stick is turned around, and the Upper limb end, with the bark still on, is pressed against the chest. The bow builder now carves the taper for the upper limb and uses the remaining 10cm of wood with the bark on as an intermediate part between carving and his own body. When finished, the bow stick is chopped off the 10cm-long support wood. After that, the bow should have precisely the length between the fingertips of both outstretched arms across the chest. The length of each tapered area of the limb is about 40cm / 16’’.

Final steps for carving a bow stick

The knife will be moved perpendicular to the stick as a final step to shave off any unnecessary material or rough spots. Up to this step, tillering was not done as we know it. Hadza people will always use one species of wood, from which they know its characteristics, and they meticulously shape these sticks in the same way. If encountering a knot in the wood, they maintain the thickness without a knot and always follow the lay and swell of the fibers.

They check the tiller just once on the finished stick. After checking, the stick is put on a bush in the sun for drying. The stick was not dried before carving, as it is easier to work on green wood. When the bow stick is considered dry enough, it will be strung. There are no nocks on either limb.

A small loop is knotted into the string on the lower limb, which gets stuck in the taper after about 3cm / 1.2’’ from the lower end of the stick. The loop will be secured with some more knots on the lower limb. Thereafter, the string will be secured to the upper limb portion by bending the stick under the knee.

The string will be knotted on the outer end, and wrappings below this knot act like a nock by holding the knot in place.

Bowstrings

These are made from animal ligaments, East African wild sisal, or Paracord.

Paracord strings

Nowadays, paracords are Hadzabe’s big favorite, as they have a constant diameter and a long lifetime. They are not affected by water and are cheap and readily available from Datoga traders. The only disadvantage is that they create an audible ‘zing’ when shot, which can spook the game.

Sisal strings

Sisal strings are processed from Sansevieria ehrenbergii leaves and have a restricted lifetime, but they are free of charge. Like paracords, they absorb the strain on the limbs when shooting.

Supraspinous ligaments

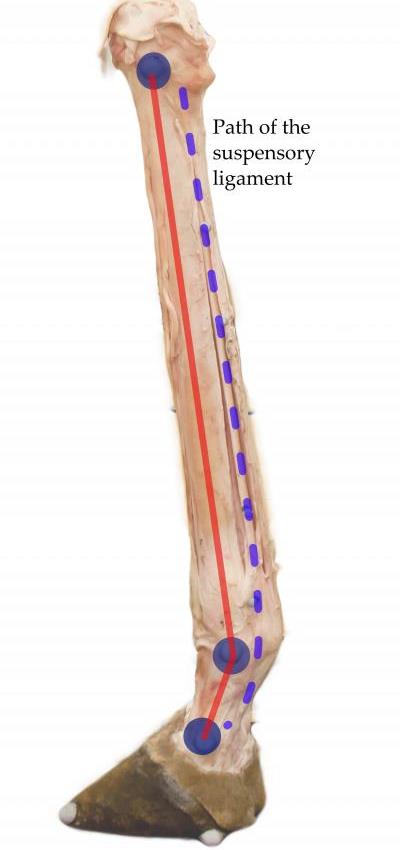

Mammals have various types of ligaments. From the head to the shoulder, there are the so-called Nuchal ligaments, which hold up the head. Their position in the picture above is marked in violet, and only the funicular part is shown, not the lamellar parts. And from the shoulders, along the spine, down to the tail are the so-called Supraspinous ligaments. These are marked red in the picture above. These supraspinous ligaments of various animal species are used for bow strings. I was told that the supraspinous ligaments of Impalas and Kudus are preferred in the area of our Hadzabe. In former times, Eland, Buffalo, and Zebra supraspinous ligaments were also used. These animals – except Zebra – are nowadays very scarce.

After removing this ligament from the dead animal, it is stretched and dried. After drying, it must be chewed to moisten and soften it. The ligament is then frayed and rolled up into a fist-sized bundle. Hadza men carry these bundles with them and use the frayed ligament to braid a bowstring or use them for their arrows. According to Daudi Peterson, only women make bowstrings. If a man is seen making one, he is either of mixed parentage or a ‘Hadza’ man by marriage.

Suspensory ligaments

In a former article on this webpage concerning the building of bushmen bows in Northern Namibia, I was describing the use of Giraffe suspensory ligaments. As not every reader will click on a link, I herewith repeat what I stated in the mentioned article:

Khoi-san bushmen in Southern Africa and the Hadza people in Tanzania use giraffe leg suspensory ligaments to bind their bow staves.

Fully grown giraffes weigh around 1000 kg (2200 lbs). As a result, each leg has to support at least 250 kilograms of weight constantly. Due to their long and thin legs, giraffes need solid bones and suspensory ligaments in these areas. This is why bushmen prefer the outer layers of the fused metatarsal and metacarpal bones, also known as giraffe cannon bones, for arrow parts. The suspensory ligament from the giraffe legs is also the preferred binding material for the bow staves.

I want to stress that these strings are not sinews but ligaments specific to giraffes. See this article. Although in nearly every piece of literature about bushmen and even in museums, this suspensory ligament is called ‘sinew.’ However, this suspensory ligament has particular characteristics. One is its length, stringiness, and uniform thickness. It is situated within a channel in the bones. When dry, it can be separated into thin, long strings. When wetting these strings, they become immediately soft and stick to each other like glue. This adhesive action can be made permanent when heating up moderately. After hardening, the ligament strings become colorless.

Finishing the bow

Hadza bow sticks are not waxed or greased, so the wood develops cracks when finally drying. Hadza people tightly wrap animal skins around the bow sticks to prevent these cracks from spreading and ensure the bow remains usable. Preferred pieces of animal skins are naturally cylindrical. These can be skin parts from around the horns of antelopes, leg skins of birds of prey, or even animal glands. If such materials are unavailable, Hadza men wrap thin stripes of rawhide around the bow and let it dry, stopping the cracking in the wood.

Lessons learned from Hadza bows for hunting

- Hadza bows are easy to build. Carving one to the correct shape takes about two hours.

- Hadza bows’ draw weight is heavier than basic-level longbows known in the West.

- Paracord or similar nylon strings are the most liked material for strings.

- The tillering of the bows is replaced by meticulously carving the exact dimensions of the tapers.

Additional information

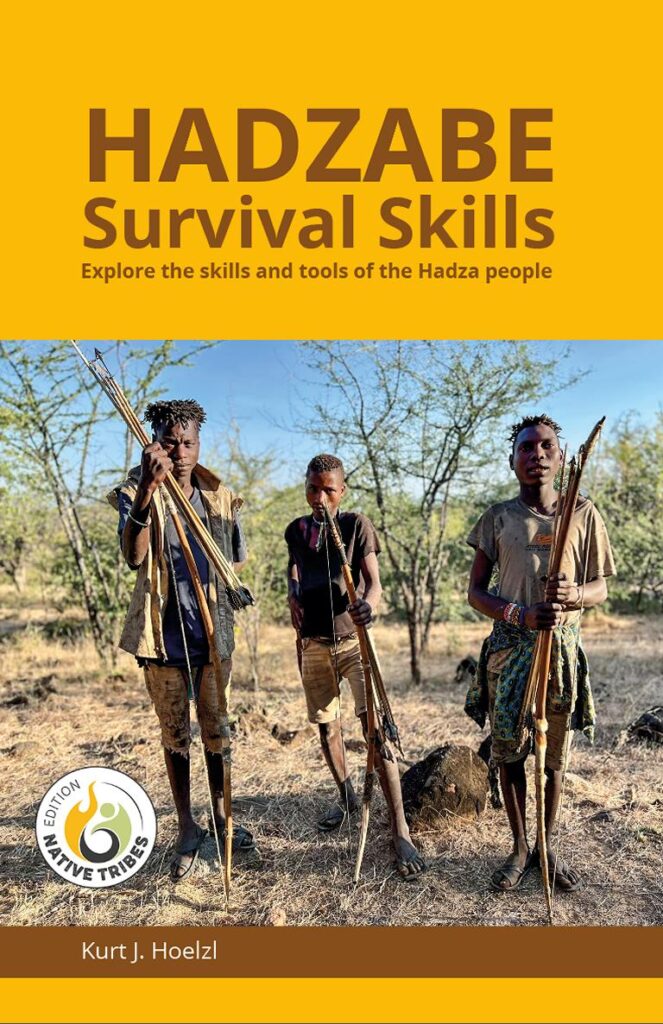

My book ‘Hadzabe Survival Skills‘ offers more skills, knowledge, tools, and techniques for the Hadzabe people’s life in their natural environment. It is available on Amazon.com and Amazon’s regional websites.

.

1 comment

Leon

Superb article on Hazada bows. I now know all the physics that I have been looking for!