Back in the nineteenth and twentieth century people tried various remedies to treat snakebite. This included cutting and sucking at the site of the bite, rubbing in Condy’s Crystals but the all-time favourite was a tight arterial tourniquet high up on the arm or leg.

Outdated treatments

First aiders often did far more damage than good, as subsequent experiments showed that none of these methods were of much help. Arterial tourniquets are particularly dangerous and often resulted in the amputation of limbs or even fatalities. By cutting off the blood flow, the lack of oxygen to the limb causes the tissue to eventually die. I asked Prof. David Warrell of Oxford University and the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) snakebite expert on his views of people using tourniquets for snakebite and his answer was as follows: “Arterial tourniquets applied at pressure above systolic blood pressure are far too dangerous ever to be recommended as I have made clear in all my publications.”

Back in the 60s and 70s, snake parks and pharmacies sold a snakebite kit that contained a small sharp knife, a reverse syringe with a spring for sucking out blood and venom (it does not work), an arterial tourniquet and two vials of polyvalent antivenom. The kits were initially packed in a metal tin that later changed to a plastic container. A near identical kit was sold by the SAVP until a few years back. Using such a kit in the field was extremely dangerous as two vials of antivenom do very little good in serious bites and lay people do not have the skills and drugs to deal with anaphylaxis.

Polyvalent antivenom

Until the early 1900s there was no effective treatment for serious snakebites throughout Africa and it was only around 1903 that antivenom became available. There were many changes in composition over the years but since the 70s we have had a polyvalent antivenom, made from the venom of ten snake species, and a monovalent antivenom for Boomslang bites, available in South Africa. It is produced by the South African Vaccine Producers (SAVP), part of our National Health Laboratories. Similar products have been produced in other countries and are now available in South Africa.

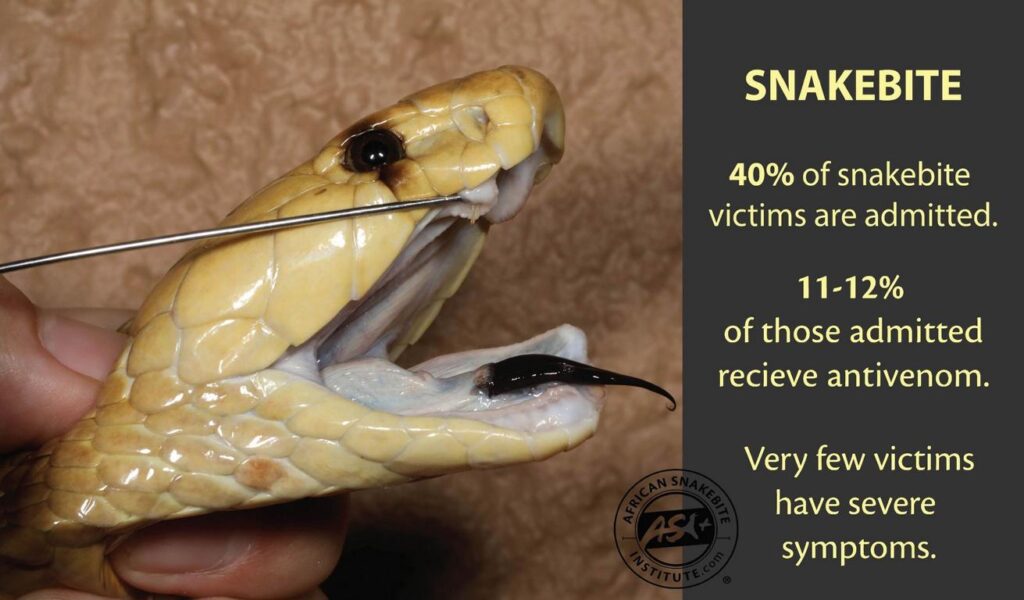

Antivenom is not a first aid product and should only be used in a hospital environment and by a medical doctor. More than nine out of ten snakebite victims do not need nor receive antivenom, as doctors treat the symptoms and not the bite. If the symptoms are severe, like progressive swelling extending more than about 10-15 cm an hour up a limb, or progressive weakness where the patient has ptosis (drooping eyelids) and a drop in oxygen levels, the doctor may well decide to go ahead and administer antivenom. Ideally, the patient should receive 6-12 vials (60-120 ml) of polyvalent antivenom administered over about 30 minutes via a saline drip, and more in the next few hours if the patient does not show signs of improvement.

The problem with our antivenom is that close to half of the patients that receive it, experience a severe allergic reaction, commonly referred to as anaphylaxis. During anaphylaxis, the patient may go into shock, the blood pressure drops, the airways narrow, and the heart may beat irregularly or quickly but weakly. Doctors are trained to deal with anaphylaxis, but it is a serious medical condition and could even be fatal. This is one of the main reasons antivenom is only administered by a doctor in a hospital environment.

First Aid recommendations

I suggest various forms of first aid for snakebite in my books, A Complete Guide to Snakes of Southern Africa and Snakes and Snakebite in Southern Africa, as well as on our website africansnakebiteinstitute.com and our free app ASI Snakes. Yesterday, one of the companies that provide first aid treatment training asked me whether the app was up to date with the latest first aid for snakebite. It is a good question and needs some explaining.

When I put together first aid protocols for snakebite, I must consider my audience. If it is a farmer tilling his fields in rural Jozini, I would strongly recommend that he gets the victim to the nearest hospital as soon as possible, bearing in mind that more than 9 out of 10 serious snakebites in southern Africa are from snakes with predominantly cytotoxic venom. In such bites, there is very little that one can do and as these venoms are slow acting, there is usually enough time to get to a hospital. The only effective treatment for serious cytotoxic bites is antivenom and that, as already mentioned, is not a first aid measure.

For hikers, fishermen, outdoor enthusiasts, and the like, I have far more suggestions – what to do in a serious Black Mamba or Cape Cobra bite and exactly what no to do. You can read all the details in the first aid section of our free app ASI Snakes. For those with more training, like paramedics, I suggest far more advanced first aid measures, like intubating, mouth-to-mouth resuscitation or using a bag valve mask for mamba and cobra victims if they stop breathing.

How do I decide what to recommend? Firstly, I look at the published literature in scientific publications. These articles document snakebites and their symptoms as well as experimental work that is done in laboratories. Then I discuss my approach to first aid for snakebite with leaders in the industry – the likes of Professor David Warrell, Dr. David Williams from the WHO, Dr. Colin Tilbury who has treated many snakebite victims and who has published widely in various journals, and Dr. Gerbus Muller, formerly from the Tygerberg Poison Centre. Then it is a matter of sifting through all the data and coming up with what I deem the best first aid measures for snakebite with our current knowledge and equipment.

First aid for snakebite also changes over time, like everything else in modern medicine. And for this reason, it is necessary for me to continually update the app and my books. ‘A Complete Guide to Snakes of Southern Africa’ was revised late last year and another revision of ‘Snakes and Snakebite in Southern Africa’ will be published early next year.

Antivenom availability

Lastly, we are often asked what the current situation is with the antivenom shortage and which hospitals stock antivenom. We never know which hospitals have antivenom and that is the least of your worries as any hospital may have 15 vials today and they are used tonight. The major shortage seems to be coming to an end and at present, SAVP are supplying antivenom for snakebite emergencies while other orders may take a few weeks.

An imported effective antivenom that costs substantially more is now also available. The cost per vial is similar to the South African product but for most bites double the volume of antivenom is required initially.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Text and all photos at this article © African Snakebite Institute. The professional background and contact information of the author of this article and owner of ASI, Johan Marais, can be found here.

Further readings about Snakes of Southern Africa on this website:

About snake home ranges and territories

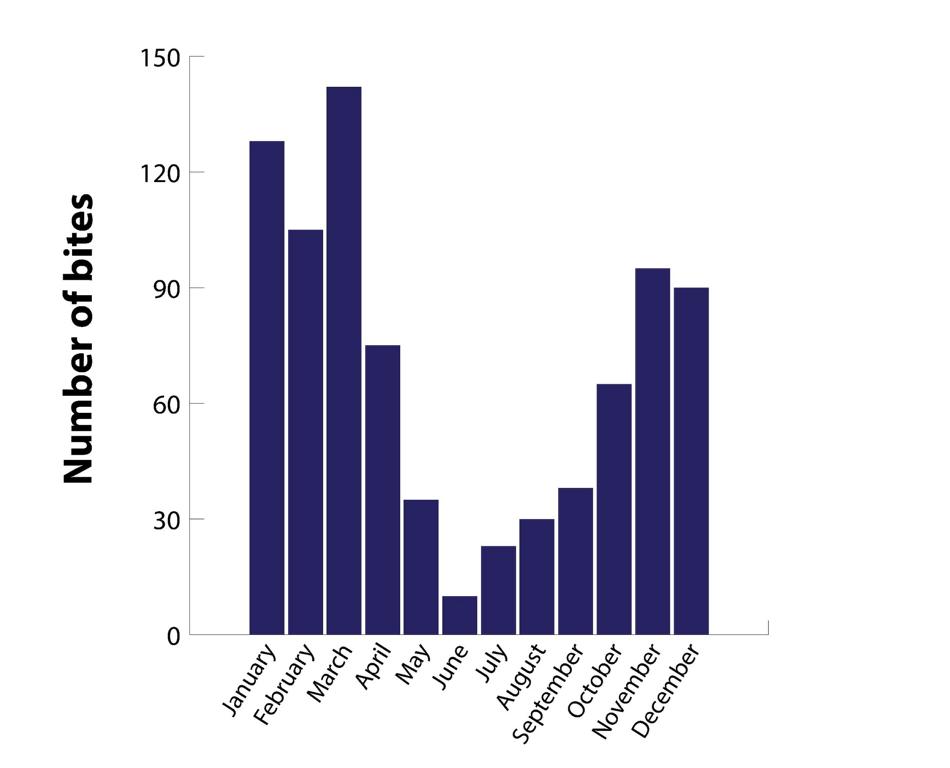

Snake Season in Southern Africa

Preventing Snakebite in Southern Africa

Field dressing and cooking a puff adder

Top ten rare snakes of Southern Africa

Small black snakes of Southern Africa

Traditional Remedies for Snakebite

.